|

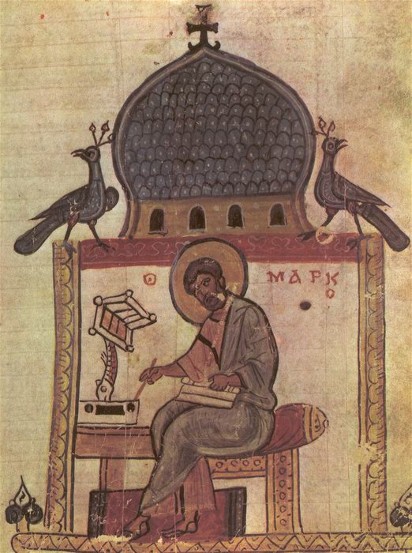

| Mark, Slavonic Dobrylo Gospel (1164 CE) |

In

compiling the unique phrases and words in Mark I found I had to differentiate

between words which are basically a similar word found in another Gospel, which

may have more to do with the voice Mark chose or other grammatical need and

those which constitute an actual thought or fact which is unique in Mark. The

latter are what we are examining here in the context of identifying finally the Catholic editor and the Author.

Note: I am publishing the third part before the second. The second is a more tedious work focused on the composition of Mark examining the sources, especially the M document shared with Matthew and elements such as the development of the feeding of the four thousand and five thousand. Occasionally I may make references to items not fully explained here which are in that as yet unpublished article - some quite fascinating.

Note: I am publishing the third part before the second. The second is a more tedious work focused on the composition of Mark examining the sources, especially the M document shared with Matthew and elements such as the development of the feeding of the four thousand and five thousand. Occasionally I may make references to items not fully explained here which are in that as yet unpublished article - some quite fascinating.

Reviewing,

the synoptic Gospel redactional model I laid out (part one) will used to

determine what the development in Mark was. This means that elements such as

Matthew chapter 5 and verses known to not have been in Marcion’s Gospel which

are found in Luke are, until shown otherwise, considered unknown to the author

of Mark – just as they would be for those following Mark priority.

So

to summarize I divide the unique material into categories probable of

composition. These are

a) Marginal notes and extraneous material

attached by a “random” scribe

b) Deliberate

late editorial addition by a Catholic editor after the main composition

c) Additions by the author of Mark

d)

Material from the sources used by Mark, passed over or unknown by Matthew or

Luke

We

are not concerned with dubious material such as the long ending (verses

16:9ff), but only with the accepted.

The

Mundane Elements

Unlike the other Gospels there are no digressions into theological points, and no unique arguments. What we do see instead is more like a series of footnotes that have made their way into the text, as means of clarifications and enhancements to the text; something of a running commentary. By far the majority of unique words and phrases found in Mark fall into the category of filling out details. Mark informs us of all sorts of little tidbits and name traditions unknown to the other Gospels, and clearly expand upon the base documents he built from. Some examples

In the wilderness he was among wild animals ἦν μετὰ τῶν θηρίων (1:13)

Levi is the son of Alphaeus τὸν τοῦ Ἀλφαίου (2:14)

David was at the alter when Abi'athar was high priest ἐπὶ Ἀβιαθὰρ ἀρχιερέως (2:26)

The tree branches were large μεγάλους and provide nests shade ὑπὸ τὴν σκιὰν αὐτοῦ (4:32) The region beyond the Galilee is called the Decap'olis ἐν τῇ Δεκαπόλει (5:20)

the garment was so white that no fuller could possibly bleach it so well

οἷα γναφεὺς ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς οὐ δύναται οὕτως λευκᾶναι (9:3)

we're told the boy has had his condition since childhood ὁ δὲ εἶπεν, Ἐκ παιδιόθεν (9:21)

Jesus became angry ἠγανάκτησεν (10:14)

Bartimaeus is the son of Timaeus ὁ υἱὸς Τιμαίου Βαρτιμαῖος (10:46)

Jesus after overturning the money tables would not permit anything carried into the temple

καὶ οὐκ ἤφιεν ἵνα τις διενέγκη σκεῦος διὰ τοῦ ἱεροῦ (11:16)

two copper coins are worth one Roman bronze quarter ὅ ἐστιν κοδράντης (12:42)

those with Jesus were Peter, James, John and Andrew

Πέτρος καὶ Ἰάκωβος καὶ Ἰωάννης καὶ Ἀνδρέας (13:5)

the nard was worth more than three hundred denarii ἐπάνω δηναρίων τριακοσίω (14:5)

Simon of Cyrene is the father of Alexander and Rufus

τὸν πατέρα Ἀλεξάνδρου καὶ Ῥούφου (15:21)

the sons of Zebedee's mother (Matthew 27:56, 20:20) is named Salome Σαλώμη (15:40) Mary is Joses' mother ἡ Ἰωσῆτος (Matthew 27:71 "the other Mary" ἡ ἄλλη Μαρία) (15:47)

In

addition several Aramaic translations are given to us formulaically

Bo-aner'ges, that is, sons of thunder Βοανηργές ὁ ἐστιν Υἱοὶ Βροντῆς (3:17)

"Tal'itha cu'mi"; which means, "Little girl

Ταλιθα κουμ, ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον Τὸ κοράσιον (5:41)

"Corban," that is, an offering Κορβᾶν, ὅ ἐστιν Δῶρον (7:11)

"Ephphatha," that is, "Be opened" Εφφαθα, ὅ ἐστιν, Διανοίχθητι (7:34)

"Abba, father, all things are possible for you"

Αββα ὁ Πατήρ, πάντα δυνατά σοι· παρένεγκε (14:36) [i]

"E'lo-i, E'lo-i, la'ma sabach-tha'ni?" which means,

"My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"

Ἐλωί ἐλωί λαμὰ σαβαχθανεί; ὅ ἐστιν μεθερμηνευόμενον

Ὁ θεός μου ὁ θεός μου, εἰς τί ἐγκατέλιπές (15:34) [ii]

I

am not certain if the Aramaic represents accretion in the source, as this is

not consistent elsewhere with M, as it appears Matthew’s source hints at more

accretion than the version Mark knew, or if it represents a deliberate effort

by Mark to represent Jesus as an Aramaic speaker, which may be important in

establishing ethnicity. This is something to note now, for later examination.

Mark often adds to stories the words Jesus and other used in conversation. For example

they fell down before him and cried out, "You are the Son of God."

προσέπιπτον αὐτῷ καὶ ἔκραζον λέγοντες ὅτι Σὺ εἶ ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ θεοῦ (3:11)

for they had said, "He has an unclean spirit." ὅτι ἔλεγον, Πνεῦμα ἀκάθαρτον ἔχει (3:30)

and said to the sea, "Peace! Be still!" εἶπεν τῇ θαλάσσῃ, Σιώπα, πεφίμωσο (4:39)

"What shall I ask?" And she said, "The head of John the baptizer"

Τί αἰτήσωμαι ἡ δὲ εἶπεν, Τὴν κεφαλὴν Ἰωάννου τοῦ βαπτίζοντος (6:24)

And he said to them, "Do you not yet understand?" καὶ ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς, Οὔπω συνίετε (8:21)

And he asked them, "What are you discussing with them?"

καὶ ἐπηρώτησεν αὐτούς, Τί συνζητεῖτε πρὸς αὐτούς (9:16)

he told his disciples for the demon "This kind cannot be driven out by anything but prayer"

καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Τοῦτο τὸ γένος ἐν οὐδενὶ δύναται ἐξελθεῖν εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ (9:33)

he asked them, "What were you discussing on the way?"

ἐπηρώτα αὐτούς, Τί ἐν τῇ ὁδῳ διελογίζεσθε (9:33)

"Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God!"

Τέκνα, πῶς δύσκολόν ἐστιν εἰς τὴν βασιλείαν τοῦ θεοῦ εἰσελθεῖν (10:24)

The

bulk of the unique elements found only in Mark are details about settings and

minor clarifications. In this category are explanations, often faulty, of

rituals and practices. For example Mark 7:2-4 has a digression into Jewish

washing purification rituals,[iii]

The information is anecdotal, and probably common knowledge for anyone with

contact with Jews. What is instructive is that the followers of Jesus, that is,

the Christians represented are not Jews and do not follow Jewish rituals such

as washing hands before eating. The need to explain the differences with Jews

(and Pharisees, explained below) represents a certain distance and time has

separated Mark’s account from Matthew 15:1-10. But in keeping with Mark’s

tendencies there is no additional theological argument made here, simply added

description of the scene.

I

leave the link to the list of unique words and phrases in Mark I

compiled, first pass and probably with a few inconsistencies, for the reader to examine and see examples for themselves.

The

Scribes in Mark

At

first I thought, as I began to write, that Mark having six unique appearances of

the scribes, or the scribes of the Pharisees, had some significance in

distancing Mark from Matthew, but this is a weak case. What I found instead was

that scribes few mentions in Luke were almost entirely missing from Marcion. [iv]

Mark 12:38 turns out to be derived from Marcion’s Gospel, switching out "lawyer"

(νομικός) in Luke 10:25 with a scribe (εἷς τῶν γραμματέων). Since lawyer appears to be a Marcionite

exclusive word (not Luke) which has the strong connotation of representing the

proto-orthodox Jewish Christians who support the Torah Law, it is very possible

that "scribe" like in the parallel Luke 20:39, likely stood in Marcion’s source

L, or that for both L and M there was no identification of the speaker simply

"one of them" as in Matthew 22:35 (εἷς ἐξ αὐτῶν). This latter scenario is what I think was the

original, where Marcion and Mark both added their identifications accordingly. Some

seem to merely be formulaic additions (e.g., 3:22 per Matthew 9:34 and 12:24 –compare

Luke 11:15 τινὲς δὲ ἐξ αὐτῶν, for possible original–, 14:43, 15:1). And those in

12:32-35 seem to be from Luke 20:39, which is a duplicate element found in

Marcion. Upon inspection this element in Mark can be explained away almost

entirely by source and formula, without any need to consider theology. [v]

Possible Contact with the Apostolikon

Mark 7:19 includes the phrase "thus he declared all foods clean" (καθαρίζων πάντα τὰ βρώματα), which appears to map to Paul's declaration - not Jesus - in 1 Corinthians 10:25, 27 that you may eat all meats. However Tertullian is unclear in AM 5.7.14 saying that he is skipping over issues, meaning whether a verse is present or not and how it is to be interpreted, immediately before mentioning "a great argument for another God is the permission to eat all meats in contradiction to the law" (Magnum argumentum dei alterius permissio omnium obsoniorum adversus legem). My analysis when building the interlinear for 1 Corinthians was that 1 Corinthians 10:22-30 was entirely inserted later by the Catholic editor based on the appearance of Pastoral words (10:23 οἰκοδομεῖ, 10:28 ἱερόθυτόν, 10:30 εὐχαριστῶ) and themes such as conscience (1:25, 1:27, 1:29 συνείδησιν) - see Winsome Munro, p169. What this verse in mark and the Catholic addition to 1 Corinthians show is that a certain selectivity of Torah Law application existed in the Catholic camp, at variance with Matthew's view. This example turns out not to show a Pauline (Marcionite) heritage for Mark, as the sentiments agree with later Catholic version of the Pauline Epistles (1 Corinthians 10:25, 27, Romans 14:14) not with the attested Marcionite versions.

Mark 14:36 declares, "Abba, father" (Αββα ὁ Πατήρ) an Aramaic phrase that appears Galatians 4:6 (AM 5.4.3) and Romans 8:15, which were present in the Marcionite collection. Again both of these verses may have been from the Catholic edition as well as the Marcionite.

Mark 14:36 declares, "Abba, father" (Αββα ὁ Πατήρ) an Aramaic phrase that appears Galatians 4:6 (AM 5.4.3) and Romans 8:15, which were present in the Marcionite collection. Again both of these verses may have been from the Catholic edition as well as the Marcionite.

Jesus as Teacher and the Crowds Approval

A primary theme of Mark's "mundane" additions is that Jesus is always mentioned as teaching (2:13 and 4:2 καὶ ἐδίδασκεν αὐτούς, 9:31 ἐδίδασκεν γὰρ, 10:1 καὶ ὡς εἰώθει πάλιν ἐδίδασκεν αὐτούς, 11:17 καὶ ἐδίδασκεν). But this teaching is often presented in the same sense as that of the teaching from a leader of Christian Sect would be viewed, evidenced by by Mark's portrayal of the doctrine taught by Jesus is of that sort. In 12:38 it is says to be wary of the scribes, not as an immediate saying to the crowd that moment but rather as part of his taught doctrine (Καὶ ἑν τῇ διδαχῇ), suggesting that Marcion/Luke 20:45-48 is an existing tenet. His teaching in parable of the Sower is said, in verse 4:2, to be from his taught doctrine (ἐν τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ), as if the parable (Marcion/Luke 8:4-8, Matthew 13:1-9) is already established.

Another primary theme in these additions is that the crowds were large and growing (e.g., 1:45, 3:9-10, 8:1, 8:34, 9:15), mostly to show the success of his mission. And these crowds sided with Jesus, such that the Jewish authorities faced hostility from them (e.g., 9:14 καὶ γραμματεῖς συνζητοῦντας πρὸς αὐτούς). This seems more a sociopolitical statement of "the people" against the Jewish leaders, under scoring that Mark is not Jewish.

Preaching the Gospel

Mark puts unique emphasis on the Gospel itself, and by this I mean a written Gospel, as the basis of Jesus' teaching. In verse 1:14 Mark announces at the start of his mission that Jesus was preaching "the gospel of God" (τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ θεοῦ), and that Christians are to "believe in the Gospel" (πιστεύετε ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ). This demonstrates that the writer holds the Jewish God as the father of Jesus, we are not dealing with a Gnostic or Marcionite God separate from the creator.

As I have explained in my notes on the Marcionite version of Romans, the Gospel of God was a name the Catholic Christians used because it implies that the Jewish God is the father; this very clear from the formula in Catholic version of Romans 1:1-3 "the Gospel of God, which he promised beforehand through his prophets and holy scriptures, concerning his son" (εὐαγγέλιον θεοῦ, ὃ προεπηγγείλατο διὰ τῶν προφητῶν αὐτοῦ ἐν γραφαῖς ἁγίαις, περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ). This stands in direct contrast to Marcion's Paul who declares in Galatians 1:7 that his Gospel is "the Gospel of Christ" (εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ Χριστοῦ) and that it was not from the scriptures but revealed to him from Christ (Galatians 1:1, 1:12). As I am simply summing up and wont digress further here, but the main point is that there is a clear distinction between the "Gospel of Christ" of the Marcionites and the "Gospel of God" of the Catholics. We can use this as a likely marker for identifying the camp for the author of a given verse. It is curious the opening of this Gospel seems to agree with Marcion Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ. [vi]

This emphasis on the Gospel shows up in an addition to saying in Mark 8:35 "For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel's (καὶ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου) will save it." This extends defense of Christ found in Matthew 16:25 and Luke 9:24, to also include what must be a written Gospel, since the statement implies a consistency in message. We are looking at a more established church than the sources M and L considered. This defense of Christ is extended to the Gospel again in Mark 10:29 (καὶ ἔνεκεν τοῦ εὐαγγελίου), confirming this is as a deliberate statement.

There is one other possible reference to Gospel content as already known, in Mark 9:12 the suffering of the son of man is prefaced by "and how it is written of" (καὶ πῶς γέγραπται ἐπὶ). There is no LXX reference, rather a Gospel reference to L source of Marcion (Luke 9:22, per Epiphanius P42 see note [iv]) "the son of man will suffer much and be killed and on the third day be raised" (Δεῖ τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου πολλὰ παθεῖν καὶ ἀποκτανθῆναι καὶ τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμέρᾳ ἐγερθῆναι) and the expanded versions of Matthew 16:21 (M source) and Mark 8:31. This is a slip that reveals the secondary nature of Mark in the verse.

A similar addition follows in Mark 9:13 about John as Elijah coming before with the statement "as it is written of him" (καθὼς γέγραπται ἐπ' αὐτόν). The should reference is to Malachi 4:5 with the Christian view that John is the return of Elijah who must proceed Christ, which explains Malachi 3:1 in Mark 1:2 and the association we find Matthew 10:10 discussed below. However the verse discusses the death of John and there is no story of a death and imprisonment of Elijah anywhere. The reference must be to the arrest of John and the beheading stories of the Gospels. This is an example of Mark not actually knowing the content of the Septuagint, but is relying on Christian interpretation, and hence the confusion.

Another primary theme in these additions is that the crowds were large and growing (e.g., 1:45, 3:9-10, 8:1, 8:34, 9:15), mostly to show the success of his mission. And these crowds sided with Jesus, such that the Jewish authorities faced hostility from them (e.g., 9:14 καὶ γραμματεῖς συνζητοῦντας πρὸς αὐτούς). This seems more a sociopolitical statement of "the people" against the Jewish leaders, under scoring that Mark is not Jewish.

Preaching the Gospel

Mark puts unique emphasis on the Gospel itself, and by this I mean a written Gospel, as the basis of Jesus' teaching. In verse 1:14 Mark announces at the start of his mission that Jesus was preaching "the gospel of God" (τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ θεοῦ), and that Christians are to "believe in the Gospel" (πιστεύετε ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ). This demonstrates that the writer holds the Jewish God as the father of Jesus, we are not dealing with a Gnostic or Marcionite God separate from the creator.

As I have explained in my notes on the Marcionite version of Romans, the Gospel of God was a name the Catholic Christians used because it implies that the Jewish God is the father; this very clear from the formula in Catholic version of Romans 1:1-3 "the Gospel of God, which he promised beforehand through his prophets and holy scriptures, concerning his son" (εὐαγγέλιον θεοῦ, ὃ προεπηγγείλατο διὰ τῶν προφητῶν αὐτοῦ ἐν γραφαῖς ἁγίαις, περὶ τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ). This stands in direct contrast to Marcion's Paul who declares in Galatians 1:7 that his Gospel is "the Gospel of Christ" (εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ Χριστοῦ) and that it was not from the scriptures but revealed to him from Christ (Galatians 1:1, 1:12). As I am simply summing up and wont digress further here, but the main point is that there is a clear distinction between the "Gospel of Christ" of the Marcionites and the "Gospel of God" of the Catholics. We can use this as a likely marker for identifying the camp for the author of a given verse. It is curious the opening of this Gospel seems to agree with Marcion Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ. [vi]

This emphasis on the Gospel shows up in an addition to saying in Mark 8:35 "For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel's (καὶ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου) will save it." This extends defense of Christ found in Matthew 16:25 and Luke 9:24, to also include what must be a written Gospel, since the statement implies a consistency in message. We are looking at a more established church than the sources M and L considered. This defense of Christ is extended to the Gospel again in Mark 10:29 (καὶ ἔνεκεν τοῦ εὐαγγελίου), confirming this is as a deliberate statement.

There is one other possible reference to Gospel content as already known, in Mark 9:12 the suffering of the son of man is prefaced by "and how it is written of" (καὶ πῶς γέγραπται ἐπὶ). There is no LXX reference, rather a Gospel reference to L source of Marcion (Luke 9:22, per Epiphanius P42 see note [iv]) "the son of man will suffer much and be killed and on the third day be raised" (Δεῖ τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου πολλὰ παθεῖν καὶ ἀποκτανθῆναι καὶ τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμέρᾳ ἐγερθῆναι) and the expanded versions of Matthew 16:21 (M source) and Mark 8:31. This is a slip that reveals the secondary nature of Mark in the verse.

A similar addition follows in Mark 9:13 about John as Elijah coming before with the statement "as it is written of him" (καθὼς γέγραπται ἐπ' αὐτόν). The should reference is to Malachi 4:5 with the Christian view that John is the return of Elijah who must proceed Christ, which explains Malachi 3:1 in Mark 1:2 and the association we find Matthew 10:10 discussed below. However the verse discusses the death of John and there is no story of a death and imprisonment of Elijah anywhere. The reference must be to the arrest of John and the beheading stories of the Gospels. This is an example of Mark not actually knowing the content of the Septuagint, but is relying on Christian interpretation, and hence the confusion.

The

Anti-Marcionite Elements from the LXX

Perhaps

the strongest case that Mark presented theological

intentions in the composition of the Gospel can be found in the story of when

Jesus is asked a tricky question of Mark 12:28-37 (Matthew 22:34-46, Luke

10:25-28). Mark has Jesus respond to the question of the greatest commandment by

prepending Jesus’ response to include Deuteronomy 6:4 LXX in verse 12:29 "Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one" (Ἄκουε, Ἰσραήλ, κύριος ὁ θεὸς ἡμῶν κύριος εἷς ἐστιν). This phrase is missing in the

militantly anti-Marcionite Matthew as his verse 22:37 has Jesus respond only

with Deuteronomy 6:5, as does also Luke 10:27 where Jesus importantly does not quote the OT

but asks the lawyer how he reads – a clear Marcionite element that survived

Luke’s revision, unlike in Luke 18:20 per Epiphanius. Deuteronomy 6:4 was a

cornerstone of the Jewish/Catholic Christian doctrine, and stands in sharp

contrast to the Marcionites and Gnostic heretics who saw the Jewish God of

Moses, and the creator, as separate from and lesser than the God of Christ.

Deuteronomy 6:4 makes it clear that there is one God and he is the God of

Israel, of the Jews, and the creator.

This

anti-Marcionite point is further driven home when the scribe replies in 12:32

quoting Deuteronomy 4:35 "You are right, Teacher; you have truly said that

he is one, and there is no other but he" (Καλῶς, διδάσκαλε, ἐπ' ἀληθείας εἶπες ὅτι εἷς ἐστὶν καὶ οὐκ ἔστιν ἄλλος πλὴν αὐτοῦ). This shows that the inclusion of Deuteronomy 6:4

was deliberate to make theological point. Further the scribe, who represents in

Mark the strongest Jewish opponents, remarkably approves of Jesus’ teaching of

the nature of God. Implied is that Christians are teaching something different

than the unity of God. A situation identical to that found in1 Timothy, 2:5 "For God is one" (εἷς γὰρ θεός), demonstrating the debating point was Catholic and used against those who separated the Creator from the father. Mark is not saying this in a vacuum, the next

commandment, "to love one's neighbor as oneself" from Leviticus 19:18,

found in the Marcionite Apostolokon (Galatians 5:14, Romans 13:9) and the

direct parallel in the Gospel (Luke 10:27).

Deuteronomy

6:4 and the reply 4:35 are fully embedded in Mark’s version, representing a

clear theological point, clarifying which God it is that one is to love with

all one’s heart. That Jesus himself is preaching it, is meant to trump

Christian opponents who see the Jewish God as the mere demiurge. Matthew’s

author showed similar sentiments, when in 22:40 he states "on

these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets," (ἐν ταύταις ταῖς δυσὶν ἐντολαῖς ὅλος ὁ νόμος κρέμαται καὶ οἱ προφῆται) making

very clear that God he speaks of is the same as the God who gave Moses the Ten Commandments

and who is the God of the Old Testament prophets.

Curiously

these accounts in Matthew and Mark stands in direct opposition to what follows

from their common source document M, and where Mark separates Christ from the

Jewish scribes, that Christ is not the son of David, that is not the Jewish

God’s Christ. [vii]

Clearly both Gospels added anti-Marcionite elements to the document they worked

from independently. In Mark’s case the first commandment is explained following

a common exegesis technique where Deuteronomy 6:5 is reflected in context of

the prior verse Deuteronomy 6:4.

The feature which stands out is that when Mark was writing, the Tricky Question in Luke 10:25-28 was already a point of contention between Marcionites and the proto-Orthodox when Mark was being written, (see AM 4.25.14-17) with the Marcionites using it as a point of emphasis to show that the Jewish God was not the father of Christ and that Mark felt the need for refutation. This clearly places authorship of Mark after the Marcionite eruption.

The feature which stands out is that when Mark was writing, the Tricky Question in Luke 10:25-28 was already a point of contention between Marcionites and the proto-Orthodox when Mark was being written, (see AM 4.25.14-17) with the Marcionites using it as a point of emphasis to show that the Jewish God was not the father of Christ and that Mark felt the need for refutation. This clearly places authorship of Mark after the Marcionite eruption.

Malachi

3:1 and Other LXX quotes in Mark

There are very few LXX quotes in Mark, and the above passage strongly indicates

that Malachi 3:1 found its way into Mark from the notes very early in

the process, either by Mark or one of the first copies. It is unlikely a

Catholic editor would have made such an error. (Note, I lean toward Mark as author for this.)

The only other unique use of the Septuagint is found in Mark 9:48, which appears to loosely quotes from Isaiah 66:24. But this turns to be based on Matthew 18:8 εἰς τὸ πῦρ τὸ αἰώνιον, expanding 18:9 "Gahanna of fire" γέενναν τοῦ πυρός, quoting the LXX to give a description of Hell / Gahanna (γέενναν). [ix] What is unique is that Mark actually quotes Isaiah’s last verse, the very same prophet he was unaware did not write Malachi 3:1 in verse 1:2. Unlike the anti-Marcionite passage in 12:29 and 12:32, this is not an embedded element in the story. But as no citation is made by Mark, much like Malachi 3:1 in verse 1:2, it seems to be more commentary in nature, and lacking textual variants, the evidence suggests this was in fact from Mark, not a later editor.

The only other unique use of the Septuagint is found in Mark 9:48, which appears to loosely quotes from Isaiah 66:24. But this turns to be based on Matthew 18:8 εἰς τὸ πῦρ τὸ αἰώνιον, expanding 18:9 "Gahanna of fire" γέενναν τοῦ πυρός, quoting the LXX to give a description of Hell / Gahanna (γέενναν). [ix] What is unique is that Mark actually quotes Isaiah’s last verse, the very same prophet he was unaware did not write Malachi 3:1 in verse 1:2. Unlike the anti-Marcionite passage in 12:29 and 12:32, this is not an embedded element in the story. But as no citation is made by Mark, much like Malachi 3:1 in verse 1:2, it seems to be more commentary in nature, and lacking textual variants, the evidence suggests this was in fact from Mark, not a later editor.

Every other Septuagint reference in Mark is paralleled

in Matthew, and a few in Marcion’s Gospel, which traces them back to the source

documents, especially the one in common with Matthew I call M. As a result no

theological position can be drawn from them for identifying Mark. [x]

Possible Theological and Political Positions

|

| Herod Agrippa II, Judea coin 94/95 CE |

With the emergence of Christian's like Mark, who are clearly not Jewish, has the Pharisees asks the question of whether they (Jews) should be paid taxesto the Romans in Mark 12:14, "Should we pay or should we not pay" (δῶμεν ἢ μὴ δῶμεν)? The question of whether it is lawful, which means Torah Law, clearly is concerned for temple taxes, which includes those collected in Synagogues to be brought to the temple as Josephus in Antiquities states "in accordance the law of their fathers" (κατὰ τὸν πάτριον αὐτῶν νόμον), should be paid to Rome (i.e., Καίσαρος). This is a situation which existed from the 3rd year of Vespasian (71 CE) until Julian (360 CE), when the Empire wide Jewish tax was paid to Rome and not to Judea, and corresponds to the main question. Mark's answer, like the other Gospels is yes, and with less ambiguity.

The Original Stories Elements

The

most perplexing element unique to Mark is the naked young man from Mark

14:51-52. This passage has baffled scholars and led to all sorts of strange

theories about its meaning and origin.[xi]

But I think the real explanation is not especially exciting. The passage is

appended and connected to the arrest of Jesus in Mark 14:43-50 on the concept

of the disciples forsaking Christ on the phrase "they all fled"

(ἔφυγον πάντες) in 14:50, with the young man "fleeing naked"

(γυμνὸς ἔφυγεν).

The

vocabulary is key to unraveling the meaning and origin of the fragment. In

14:51 we are told "a young man followed him,

with nothing but a linen cloth over his naked body" Καὶ νεανίσκος τις συνηκολούθει αὐτῷ περιβεβλημένος σινδόνα ἐπὶ γυμνοῦ. This immediately reminds us of verse 16:5 where at

the tomb the women see "a young man sitting on the right having been

clothed in a white robe" νεανίσκον καθήμενον ἐν τοῖς δεξιοῖς περιβεβλημένον στολὴν λευκήν. The vocabulary overlap is not accidental. Clearly

in verse 16:5 the reference to the young man in a white robe is the same as the

angel in the version of the scene in Matthew 28:5. And this angelic clothing in

white is explained in Revelation 7:14, where those saints referred to in verses

7:9-13 having gone through great tribulation "they have washed their

robes and made them white in the blood of the lamb" καὶ ἔπλυναν τὰς στολὰς αὐτῶν καὶ ἐλεύκαναν αὐτὰς ἐν τῷ αἵματι τοῦ ἀρνίου. As I have covered elsewhere, the book of

Revelation while deals with cosmic events, and blood of the lamb is Christ’s

blood, and that is what makes the garments so dazzling white, like we see with

the young man at the tomb.

What

is left is the reference to nakedness which is only confusing because Mark did

not comment on it. However the theology is clear enough and can be traced to 2

Corinthians 5:1-10, [xii] specifically 5:3, "if indeed having been unclothed we will

not be found naked" εἴ γε καὶ ἐνδυσάμενοι οὐ γυμνοὶ εὑρεθησόμεθα. The clothing here is spiritual, as

stated in the prior verses, "we have a house (οἰκίαν) not made with hands eternal in the heavens.

For indeed we groan, longing to be clothed (οἰκητήριον) in our dwelling from heaven."

The reference then to the linen cloth covering the naked body of the young man in

Mark 14:51 represents a heavenly house for the body. But in forsaking Christ

and fleeing "he leaves behind the linen cloth" ὁ δὲ καταλιπὼν τὴν σινδόνα and so doing flees without Christ’s

heavenly cover is "found naked"; the very condition spoken of

in 2 Corinthians 5:4 of "we do want to be unclothed but cloth"

οὐ θέλομεν ἐκδύσασθαι ἀλλ' ἐπενδύσασθαι, because in verse 5:6 "we

know that being at home in the body we are away from the Lord" εἰδότες ὅτι ἐνδημοῦντες ἐν τῷ σώματι ἐκδημοῦμεν ἀπὸ τοῦ κυρίου.

The

young man in forsaking Christ and fleeing with the disciples is thus away from

the Lord and found naked. It is a theological point which Mark does not seem to

grasp, as he makes no comment on the allusion. There is some evidence of Mark

wording in both verses 14:51 and 16:5, specifically περιβεβλημένος, but nothing to indicate he was aware

of its implications. He treats the passage as a mundane addition. Thus I

conclude that it was part of the source document Mark worked from, something

which grew organically after Marcion and Matthew gospels were written – the

source likely lost when Luke redacted Marcion.

Mark

8:22-26 is another healing of a blind man that shares some close similarities

with Mark 10:46, 49-52 healing of Bartimaeus upon leaving Jericho without the

son of David references. Like Matthew 9:27-31 with respect to Matthew 20:29-34,

this story appears to be a more primitive version of the Jericho healing, only

unlike Matthew 9:27-31 it is still attached to the Four Thousand Loop, albeit

appended at the end.

Conclusions

The

first conclusion I draw about the composition of Mark is that it appears to be

a conflation of source documents we can largely reconstruct from common text with

Matthew (M) and Luke/Marcion (L) sources. The general lack of secondary

theological layer, the primary motivator for any such expansion, largely rules out a Catholic editor. Nearly every

expansion can be explained away as transition words to allow smoother

conflation, accretion and minor variances in the source documents, and mostly

detail enhancement to stories (e.g., who was present, what words were said, the

actions Jesus took in a healing, etc), and to show the popularity of Jesus with

the masses. What is left is very little which could possibly be assigned a later

Catholic editor. Thus I conclude there was no Catholic layer, and no Catholic editor.

There

are several salient features in the unique material of Mark which bear note.

The first of which is the variance from Matthew due quite possibly to differences in the version of the common source. For example Matthew 9:27-31 and the parallel Matthew 20:29-34 both have two blind men, while Mark 8:22-26 and the parallel 10:46-52 has only one blind man (as also Luke 18:35-43). It is unlikely Matthew changed both stories to two blind men, as his story telling was theologically driven, but rather the source document differed from Mark (Matthew's source seems later here). Similar adjustments no doubt drive several variants in Mark. (Note, these are covered in part two not yet published).

About all we can conclude is that the author of Mark appears to be a gentile Christian, who does not make copious use

of the Septuagint for proof texts unlike Matthew and Luke. His blunder in verse 1:2 suggests the LXX was not one of his sources, or was a book he was only acquainted with and not deeply knowledgeable, understood most likely through Christian commentary. But as can be seen from the anti-Marcionite elements

he sides with the Jewish God as father of Christ, and so is firmly

Catholic. But he also makes a strong effort to distance himself from Judaism unlike Matthew (e.g., Mark 7:8, 7:19).

This brings me to the question of motivation for writing this Gospel, conflating the M and L sources. The answer is possibly found in the opening of the Gospel of Luke, when the author of that Gospel states, "many have attempted to compile a narrative" (πολλοὶ ἐπεχείρησαν ἀνατάξασθαι διήγησιν). Mark's Gospel likely represents one of those compilations mentioned by Luke. [xiii] Luke 1:3 straight forward states in that the work was commissioned by one Theophilus, and one can assume similar motivation for Mark to cobble together the accounts M and L which he knew into a single narrative. But unlike Luke, who had an adoptionist message implanted on his Gospel, Mark appears only to have been motivated to harmonize the existing accounts without implanting a specific message beyond answering detail questions which had arisen since those ür-Gospels M and L went into circulation.

The audience was Gentile Christian and had concerns accordingly, such as whether to pay Fiscus Iudaicus (12:14 δῶμεν ἢ μὴ δῶμεν) and whether Torah Law applied to diet (7:19 καθαρίζων πάντα τὰ βρώματα) and beyond that curiosity of names, places, and Jewish customs. In the end all we can say is the Gospel was written after the Bar Kokhba revolt, after the Marcionite eruption, and before the Catholic letters of Paul and the Gospel of Luke were written, and that the author was a Gentile proto-Orthodox Christian without the legalistic concerns of Matthew. Assigning a more specific camp to the author is impossible. But it is worth noting that even with Jesus specified as a son of David, from Nazareth, and with the Jewish God as father, this author was comfortable without a protoevangelium or a post resurrection story which caused later Catholic scribes to append one - a clear sign that Orthodoxy was far from settled in second half of the second century.

I am comfortable placing a maximum date boundary of between 145 AD and 165 AD. Most likely the composition date was between 150-160 AD, as there is nothing to suggest the Parthian War has yet erupted (suggested by a few elements in Catholic Luke) and so Antoninus is still most likely on the throne, and Marcion has already split as suggested in both the terms "Gospel of God" and the anti-Marcionite references to Deuteronomy 6:4. It's a bit anticlimactic of an answer and somewhat unsatisfying to say, but that is the best we can do.

This brings me to the question of motivation for writing this Gospel, conflating the M and L sources. The answer is possibly found in the opening of the Gospel of Luke, when the author of that Gospel states, "many have attempted to compile a narrative" (πολλοὶ ἐπεχείρησαν ἀνατάξασθαι διήγησιν). Mark's Gospel likely represents one of those compilations mentioned by Luke. [xiii] Luke 1:3 straight forward states in that the work was commissioned by one Theophilus, and one can assume similar motivation for Mark to cobble together the accounts M and L which he knew into a single narrative. But unlike Luke, who had an adoptionist message implanted on his Gospel, Mark appears only to have been motivated to harmonize the existing accounts without implanting a specific message beyond answering detail questions which had arisen since those ür-Gospels M and L went into circulation.

The audience was Gentile Christian and had concerns accordingly, such as whether to pay Fiscus Iudaicus (12:14 δῶμεν ἢ μὴ δῶμεν) and whether Torah Law applied to diet (7:19 καθαρίζων πάντα τὰ βρώματα) and beyond that curiosity of names, places, and Jewish customs. In the end all we can say is the Gospel was written after the Bar Kokhba revolt, after the Marcionite eruption, and before the Catholic letters of Paul and the Gospel of Luke were written, and that the author was a Gentile proto-Orthodox Christian without the legalistic concerns of Matthew. Assigning a more specific camp to the author is impossible. But it is worth noting that even with Jesus specified as a son of David, from Nazareth, and with the Jewish God as father, this author was comfortable without a protoevangelium or a post resurrection story which caused later Catholic scribes to append one - a clear sign that Orthodoxy was far from settled in second half of the second century.

I am comfortable placing a maximum date boundary of between 145 AD and 165 AD. Most likely the composition date was between 150-160 AD, as there is nothing to suggest the Parthian War has yet erupted (suggested by a few elements in Catholic Luke) and so Antoninus is still most likely on the throne, and Marcion has already split as suggested in both the terms "Gospel of God" and the anti-Marcionite references to Deuteronomy 6:4. It's a bit anticlimactic of an answer and somewhat unsatisfying to say, but that is the best we can do.

Addendum:

I will at some point release the middle section, part two of this series, when I am comfortable with the format. It will be the driest of the three, but will go into depth on the content of the two ür-Gospels M and L. And it has to be, since it really is meant to build a strong case to answer traditionalist defenders. There is a lot of foundation which has to be laid. One curious element of M, which includes the embedding of the four thousand loop, is that the feeding of the four/five thousand original story lacked any reference to fish. (Couldn't resist that spoiler)

I intend to return to my Marcionite Apostolikon interlinear work and push out Laodiceans and the Thessalonians. My aim is to complete and publish the entire collection by mid year. I need the deadline, as I am more than halfway through all three of those epistles and need to complete them. Colossians will for sure be the most difficult, and likely the last one I'll push out.

I am disappointed that I was unable to assign a specific camp to Mark, although there are some similarities to Carpocrates in that Jesus is educated in the way of the Jews but regards them with contempt; and that Jesus is show using incantations to remove daemons. But there are also significant differences, and not group is mentioned with all the characteristics and with the Jewish God as father. There simply isn't enough evidence one way or the other for docetism, so I was left without any further ability to identify the author's affiliation beyond proto-Orthodox gentile who does not know the OT directly. Anything more would be wild speculation that I am not comfortable with. The lack of a later Catholic layer also does not help, since there is no tendency which is trying to be corrected to help identify the author's leaning. I hope to revise this view with a more definitive answer in the future

I intend to return to my Marcionite Apostolikon interlinear work and push out Laodiceans and the Thessalonians. My aim is to complete and publish the entire collection by mid year. I need the deadline, as I am more than halfway through all three of those epistles and need to complete them. Colossians will for sure be the most difficult, and likely the last one I'll push out.

I am disappointed that I was unable to assign a specific camp to Mark, although there are some similarities to Carpocrates in that Jesus is educated in the way of the Jews but regards them with contempt; and that Jesus is show using incantations to remove daemons. But there are also significant differences, and not group is mentioned with all the characteristics and with the Jewish God as father. There simply isn't enough evidence one way or the other for docetism, so I was left without any further ability to identify the author's affiliation beyond proto-Orthodox gentile who does not know the OT directly. Anything more would be wild speculation that I am not comfortable with. The lack of a later Catholic layer also does not help, since there is no tendency which is trying to be corrected to help identify the author's leaning. I hope to revise this view with a more definitive answer in the future

Footnotes:

[ii] Mark 15:24 is not unique, but

shares this Aramaic explanation nearly identically with Matthew 27:46 (Ηλι ηλι λεμὰ σαβαχθανι; τοῦτ' ἔστιν, Θεέ μου θεέ μου, ἱνατί με ἐγκατέλιπες). Matthew

elsewhere makes no effort to demonstrate that Jesus' native tongue was Aramaic.

This poses a vexing question of whether these are original to Mark or accretion

in the version of the source M which Mark knew compared to the version Matthew

knew?

[iv] The only attested presence of

scribes in Marcion is from Luke 20:39, AM 4.38.9 'the Scribes exclaimed,

"Master, Thou hast well said."' Atque

adeo scribae, Magister, inquiunt, bene dixisti. Note,

the scribe here is not an opponent of Jesus in Luke’s account.

Epiphanius

P42 reads 20:19 Καὶ ἐζήτησαν ἐπιβαλεῖν ἐπ' αὐτὸν τὰς χεῖρας, καὶ ἐφοβήθησαν

without "the scribes and the chief priests" (οἱ γραμματεῖς καὶ οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς) or

"in that very hour" (ἐν αὐτῇ τῇ ὥρᾳ)

and they merely are afraid, not "of the people" (τὸν λαόν).

Epiphanius' reading maps closely to Mark 12:12 Καὶ ἐζήτουν αὐτὸν κρατῆσαι. Tertullian in AM 4.12.5 seems

to read Luke 6:7 as only the Pharisees (accusant pharisaei) accusing Jesus, in line with

Matthew 12:14. Curiously Mark 3:6 has the Pharisees in strange bedfellow alliance

with the Herodians. These cast grave doubts that any instances of scribes as

opponents were in Marcion's Gospel.

The

evidence is inconsistence for Luke 9:22, with Tertullian and Epiphanius disagreeing.

Tertullian AM 4.21.7 reads in agreement with the received text: "the Son

of man must suffer many things, and be rejected of the elders, and scribes, and

priests, and be slain, and be raised again the third day." quia oporteret filium hominis multa pati, et reprobari a presbyteris et scribis et sacerdotibus, et interfici, et post tertium

diem resurgere;

Epiphanius P42 appears to read a much abbreviated version "it is necessary

for the son of many to suffer many things, and to be killed, and the third day

be raised" Δεῖ τὸν ἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου πολλὰ παθεῖν, καὶ ἀποκτανθῆναι, καὶ μετὰ

τρεῖς ἡμέρας ἐγερθῆναι,

omitting the "and be rejected of the elders, and scribes, and priests."

Epiphanius' reading is closer to 1 Corinthians 15:3-4 in Marcionite form ὅτι Χριστὸς ἀπέθανεν καὶ ἐτάφη καὶ ἐγήγερται τῇ ἡμέρᾳ τῇ τρίτῃ.

The rejection by the priests and the scribes seems to be outside Marcion,

making one wonder if Tertullian is not reverting to the Catholic text. I find myself

siding with Epiphanius on this reading on the weight of Marcion's reading of 1

Corinthians 15:3-4, and against Tertullian's even though he agree with Matthew

16:21 and Mark 8:31. There is some instability in the witnesses: Clement seems

to agree with Marcion per Epiphanius; family 1 is missing 'scribes', 565 is

missing the 'chief priests'. The received text appears to be an expansion of

the original creed, and there is nothing in that expansion which would have met

any objection from Marcion.

I

am uncertain about the 'woe to the scribes' saying in Luke 20:46 which is

essentially identical form as Mark 12:38. It would be unusual for Mark to be original

and Luke copy, but there is possibly evidence in the Wicked Tenants. This needs more study.

All

the others lack any mention, one way or the other in the anti-Marcionite Literature,

so determining their presence has to move to internal evidence and consistency

with Marcionite writing. Tertullian in AM 4.12.5 seems to read only 'Pharisees'

in verse 6:7, which would align Marcion's text with Matthew 12:14, and even the

expanded Mark 3:6 which has the Pharisees forming an unlikely alliance with the

Herodians (huh?). Luke 20:1 Tertullian seems to read in agreement with Matthew

21:23 "the chief priests and the elders of the people" without

scribes, and AM 4.38.1 mentions only Pharisees. AM 4.41.2 only reports Jesus was

brought before the Sanhedrin in verse 22:66, a reading closer to Matthew 26:59.

Verses 15:2 and 23:10 seem most likely to be later insertions by Luke. There is

no evidence one way or the other for the reading of Luke 5:21, 5:30, 22:2, but

that is a very weak case for the word being present (Peter Head’s easy acceptance

of unattested material being included in Marcion's Gospel by default aside – it’s

based on the circular logic of his presumed model … had to take a shot at him

somewhere; but really it’s the same for all such supporters of Luke priority

over Marcion side Harnack). It should be noted that scribes are entirely

missing from the Gospel of John as well (verse 8:2 is part of the 5th

century adulterous woman insertion).

[v] The one instance not

explained away is verse 9:14 'and scribes arguing

with them' καὶ γραμματεῖς συνζητοῦντας πρὸς αὐτούς. This is unique to

Mark, with the scribes arguing with the crowd. My current speculation is the

crowds in Mark represent Christians and the scribes some hither to now

unidentified sect or other movement which opposes Mark. We have few clues to

work with here.

[vi] Mark 1:1 reads Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, which agrees with Marcion's Paul, and I think is the earliest form of the Gospel title was not τοῦ εὐαγγελίου τοῦ κυρίου as implied by Tertullian, but more likely τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Χριστοῦ in agreement with the Apostolikon. This is probably the the title the ür-Gospels had. Mark added Ἰησοῦ and orthodox scribes worried about Adoptionist readings (and I think also to make clear that Jesus was the Jewish God's son) added υἱοῦ θεοῦ. See Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, pages 72-75, for a complete analysis.

[vi] Mark 1:1 reads Ἀρχὴ τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, which agrees with Marcion's Paul, and I think is the earliest form of the Gospel title was not τοῦ εὐαγγελίου τοῦ κυρίου as implied by Tertullian, but more likely τοῦ εὐαγγελίου Χριστοῦ in agreement with the Apostolikon. This is probably the the title the ür-Gospels had. Mark added Ἰησοῦ and orthodox scribes worried about Adoptionist readings (and I think also to make clear that Jesus was the Jewish God's son) added υἱοῦ θεοῦ. See Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture, pages 72-75, for a complete analysis.

[vii] These source document for

Matthew 22:42-45 and the parallel in 9:27,

Mark 12:35-37, and Luke 20:44, appear on the surface to be inconsistent, as

Jesus is called the "son of David" by the blind man in the healing at

Jericho. But this is not the case, as the key element in the allegory is that

those blind to the truth about Christ are the ones who think he is the

"son of David." This is clear in the Mark/Luke accounts, as gaining

faith in Christ cures the blindness, and they then "followed him,"

that is the true Christ, not the Davidic King. John 7:40-41underlines this very

point, that Jesus is not the son of David, not from Bethlehem, but Galilee.

Further in John 8:44 the God and father of the Jews is declared both a liar and

a murderer.

Matthew being Jewish Christian also includes the after the healing of the two blind men at Jericho (note, he removed the faith element, understanding its implication), when Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, he has the crowd declare Jesus the son of David (21:9), and before (21:5) to tell the daughters of Zion the King is coming. Clearly Matthew sees Jesus as the Davidic king. Mark’s version lacks this detail, but mentions the restoration of "the Kingdom of our father David" in 11:10, clearly the same sentiment. This story is not found in Marcion (Epiphanius reports Luke 19:29-46 were not present). This shows an expansion in the source M compared to L.

Matthew being Jewish Christian also includes the after the healing of the two blind men at Jericho (note, he removed the faith element, understanding its implication), when Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, he has the crowd declare Jesus the son of David (21:9), and before (21:5) to tell the daughters of Zion the King is coming. Clearly Matthew sees Jesus as the Davidic king. Mark’s version lacks this detail, but mentions the restoration of "the Kingdom of our father David" in 11:10, clearly the same sentiment. This story is not found in Marcion (Epiphanius reports Luke 19:29-46 were not present). This shows an expansion in the source M compared to L.

[ix] Interestingly, the first part of Isaiah 66:24 used by Mark, "where their worm never dies" ὅπου ὁ σκώληξ αὐτῶν οὐ τελευτᾷ appears to have been paraphrased by the Apocalypse of Peter when speaking of the fate of people who persecuted (οἱ διώξαντες τοὺς δικαίους) the righteous "and their bowels are forever consumed by sleepless worms" καὶ ἐσθιόμενοι τὰ σπλάγχνα ὑπὸ σκωλήκων ἀκοιμήτων

[x] The LXX quotes and allusions in Mark all map to Matthew and the M document, where they almost all came from. Several are missing from Marcion (Luke 3:4, 19:38, 46, 20:17, 37-38, 23:34 are all attested as not being in Marcion), and only a few are in Marcion (Luke 8:10 which is the Gospel writer's comment, 10:27 utter by a lawyer, 18:20 uttered by a scribe in Marcion's version, 21:27 = Daniel 7:13 the only one uttered by Jesus).

[xi] Secret Mark is one such bizarre explanation which has unfortunately colored, or rather poisoned the well of scholarship. The

story surrounding the supposed discovery of a Manuscript by Morton Smith

and its subsequent vanishing after printing is remarkably similar the

story of Pliny’s supposed tenth book, which was published by Giovanni Giocondo in the 15th century and the manuscript vanished.

[xiii] Luke alone among the Synoptic Gospels did not use one of the two ür-Gospels M and L, rather he worked from compiled versions of Marcion Gospel, The Gospel of the Hebrews, Matthew, and in my view Mark also for a handful elements such as Nazareth and stories like the Wicked Tenants. In large measure though he built on the Gospel of the Lord, which was Marcion's and took pieces here and there from the others and wove it into his own original narrative. This opinion is however not rigorously supported, so I present it as merely my preliminary observation.

What is your take on the Letter to the Hebrews, where it appears a point of contention is "the readers are in danger of reverting to participation in the Levitical sacrificial system, which would only be possible for Jews" and before the destruction of the temple? This would have to be an allegory? Of a tax?

ReplyDeleteOf course its allegorical, at least in the mind of the final redactor. Hebrews is a funny book, which appears to be unknown until the start of the 3rd century. Tertullian around 211 CE and Hyppolytus around 235 CE are the first attestations to the books existence. The vocabulary shares much with Luke (post Marcion) and Acts, and there are several themes common with the post Marcionite Jewish Christian positions. These all point toward a (final) composition in the 4th quarter of the 2nd century.

DeleteLike Revelation it is a book of multiple layers and an evolving theology. There is considerable contact to the Pauline letters in Catholic form (circa 175 CE) which you can see in the table on Barry Smith's introduction page (http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/NewTestament/Hebrews/Introduction.htm). Read also section 5.2

To be honest I have not spent a lot of time on Hebrews. But I think it is enormously important for understanding the developing Catholic exegesis of the 2nd century.

I can't wait to read part two of Mark because I struggle with placement of Mark more than any other. I guess it is just reading Mark priority for so long.

ReplyDeleteI do need to get back to finishing Mark. Since I wrote this I read Thomas L Thompson's book, the Messiah Myth, and it gave me better understanding of John the Baptist. He sort of destroys Robert Price's idea that Jesus is John the Baptist "resurrected," mostly by showing he is a literary stand in for the Elijah role. But I digress.

DeleteI am about 75% done with a very long post on the Gospel of John, in honor of my late father. It's a survey of the content, or rather the pre-Catholic layer(s). Reading it with the keys to the terminology makes it extremely coherent. I had before thought it was five layers. I am now convinced the commentary elements (e.g., 1:1-18, 3:16-21, 3:31-26, chapter 17) are actually part of the composition, and so are the "signs" comments (there is no missing Gospel) - the comments are not part of the "4000" loop that includes the feeding and walking on water, but John's. The Catholic layer is much smaller than I had thought for the first 19 chapters (chapter 21 is an obvious tack on, and chapter 20 is a heavily doctored mess). It's pretty clear the author of John knows the Marcionite NT and probably Matthew. I date the first composition around 160-165 CE, and the Catholic layer around 170-180 CE. I can't place it later than that given Irenaeus' witness (c. 185 CE).

The reason I mention John, is because I have changed my mind on how to do part 2 of Mark. I think the key is to focus on the composition of the ür-Gospel M shared by Matthew and Mark which includes the signs/4000 loop. I will focus my 2nd part on the writing of M as a development upon L in the time frame of the immediate post Bar Kokhba war. You'll probably have to wait 6 weeks or so for that (I have to scrap my draft of part two and start over).

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete