|

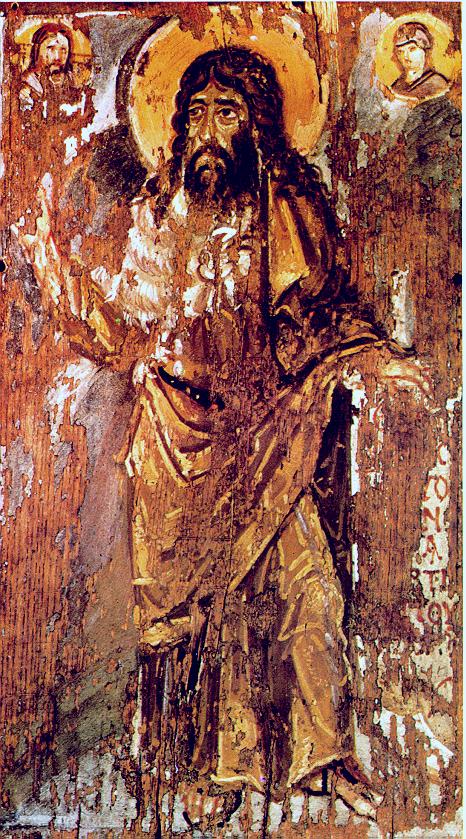

| John the Baptist, 6th Century Icon St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai |

The Evolving Character of John the Baptist

The character of John the Baptist figures prominently in the Gospels. We are all familiar with the scene on the Jordan where John is Baptizing, and then when Jesus is Baptized the sky opens and a voice is heard. And we are familiar with the Malachi and Isaiah references that introduce John and his preaching. But this is information that can get in the way of understanding how the character came to be so prominent in the Gospels and understanding how his role started and evolved.

So for this presentation, I am going ask you to forget everything we think we know about John and start with a fresh reading, as if for the first time. Beginning the Marcionite Gospel, and analyzing only what we find in that Gospel to understand John within the context of that writing. From there we will expand into the other Gospels to see how the character developed.

Marcion’s gospel begins with Jesus descending into Capernaum, with no Baptism or temptation story preceding. And yet John is not entirely absent in Marcion. Tertullian (Adversus Marcionem 4.11.4) Concerning Luke 5:33 exclaims

Unde autem et Ioannes venit in medium? Subito Christus, subito et Ioannes.Tertullian was not exaggerating, it is a surprise to see seemingly out of nowhere and with no introduction, given in Marcion’s Gospel there is no baptism scene nor any birth narratives, that we see a crowd suddenly compare John’s disciples to Jesus’,

Whence, too, does John come upon the scene? Christ, suddenly; and just as suddenly, John!

And they said to him, "The disciples of John fast often and offer prayers, [It is striking that the Marcionite author feels no need to introduce John, because his audience is presumed to already know who he is – an observation that will become clearer as we survey the rest of the gospel. Who is this John then whom the audience already knows?likewise those of the Pharisees], but yours eat and drink." [1]

The first thing we notice that like Jesus, John has disciples. This indicates that each holds a similar status in their respective communities, essentially comparable to sect leaders complete with disciples, exactly as was common in the fledgling Christian communities of the mid-2nd century.

The second thing we notice is that in Marcion’s gospel [2] John himself never actually appears on the stage, only his disciples. In verse 5:33 it is John’s disciples who are compared to Jesus’ disciples. Next in Luke 7:18-19, it is through his disciples that he asks about Christ. In verses 7:22-28 it is Jesus replying to John’s disciples and then speaking about John. In verses 9:7-8 it is Herod who mentions his beheading of John in passing. In verse 9:19 the disciples mention John among those whom the people think Jesus may be. Again in verse 11:1 one of the disciples asks Jesus to “teach us to pray as John taught his disciples.” Verse 16:16 simply tells us “the Law and Prophets were until John,” as if he is gone. And finally verses 20:1-8 features Jewish religious figures asking Jesus about John’s Baptism. In none of these scenes is John actually present.

The third thing we notice is that John, or his disciples, are always put forward in comparison to Jesus and his disciples. What we can determine about John comes from the contrast to and the replies from Jesus. John is in fact defined by Jesus’ words. So we only know him in the same sense we know of heretics from the writings of their orthodox opponents, where we have to read between the lines of the contrasts to decipher their featured teachings.

John Already Dead

Why is it that John never appears in Marcion’s gospel? And why is it we only see his disciples? One very real possibility is that John is already left the scene when Jesus begins his mission. He is definitely dead before the middle of the Gospel, as the story of Herod’s interest in Luke 9:7-9 tells us this plainly.

Now Herod [Herod’s statement differs slightly from Matthew and Mark, where he declares that Jesus must be John the Baptist raised from the dead. But in all accounts John is dead, and Herod knows of Jesus only after John. And he compares, as others do, Jesus to John, and on the same general terms. But in Marcion, Herod does not know who Jesus is, underscoring the concept of an alien God’s Christ, as opposed to the one Herod knows for John.the tetrarch] heard of all that was done, and he was perplexed, because it was said by some that John had been raised from the dead, by some that Eli'jah had appeared, and by others that one of the old prophets had risen. Herod said, "John I beheaded; but who is this about whom I hear such things?" [3]

Jesus asks the same question, attested in Dialogue Adamantius 2.13 as recorded by the Marcionite Markus,

In the Gospel, Christ says, "'Who do men say that I, the son of man, am?' The disciples said, 'John the Baptist: but some say Elijah, while others claim that one of prophets of old has arisen.' And he said to them, 'But who do you say I am?' Answering Peter said, 'The Christ.' [4]In addition to having John held in company with Elijah or some ancient prophet having risen, the author makes it clear Jesus is thought of as John by many. This is probably allegorical, but importance is John is widely understood to be a teacher on the same order as Jesus.

"Can you make wedding guests fast while the bridegroom is with them? The days will come, when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will fast in those days."Jesus’ reply tells us fasting is something to be done when the central person or figure for the feast – which is largely what a wedding party is – is no longer around. It is clearly an illusion to death. Jesus is alive and his disciples eat and drink; but John’s fast often, suggesting none to subtly he is already dead.

One mechanism the Gospel writers used to create separation was to have John imprisoned, which the Canonical synoptic Gospels do around the time of Jesus’ Baptism; Luke 3:20 even before Jesus is baptized(!). And we see in when John is placed off stage in the account of Luke 7:18ff, as recorded in Dialogue Adamantius 1.26,

"Now when he (John) had heard in prison the works of Christ, he sent his disciples to him, saying 'Are you he who is to come, or look we for another? '" [5]From a composition standpoint the text follows more closely Matthew 11:2-3 than Luke 7:18-19, including the detail from Matthew’s account of John being imprisoned. While this wording is from Markus the Marcionite champion, and there is precedent for Marcionite wording to more closely correspond to Matthew’s gospel than Luke’s, [6] I suspect that the words “in prison” (ἐν τῷ δεσμωτηρίῳ) were not in Marcion, but added to conform to Matthew by the writer of Adamantius, as Tertullian comments on the passage in AM 4.18.4-6 make no mention of John’s imprisonment. For Matthew, explaining John’s distance is handled by his imprisonment in verse 4:12, immediately before Jesus’ ministry begins. Luke 3:19-20 curiously places John’s arrest immediately before Jesus’ is baptized (by whom, himself?). But in Marcion there is neither an imprisonment of John, nor a Baptism scene, nor mention of Herodias marriage, so there seems no reason for the words “in prison” to be in Marcion’s text; and if he words were there, I can find even less reason for Luke to have omitted them in his redaction.

But even without the artificial imprisonment the Matthew reading here creates, John is off the stage, and his disciples stand in and represent him. The question they ask, which is in the “we” form, is for themselves as much as John when they say, “Are you he who is to come, or are we to look for another?” And even though Jesus addresses his response as if to John, he replies the disciples and asks them to judge what they have seen and heard themselves.

"Go and tell John what you have seen and heard:It is really a call for John’s disciples to believe Jesus. Most of these references are to events in prior passages. But the healing of a blind man does not occur until much later, in Luke 18:35-42. [7] This suggests the passage is not chronologically in the correct timeline sequence. It was likely placed here for theological sequencing purposes, as we shall see shortly below.

the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, the poor have gospel preached to them."

Of the signs, the most important theologically for the Marcionites was the gospel being preached. This is the key difference with what John had taught, and was the pitch to those who were disciple of John to follow Jesus. This difference John and Jesus is underscored in verse 16:16 when Jesus says,

"The law and the prophets were until John; since then the gospel of the kingdom of God is preached, and every one enters it violently." [8]To the Marcionite reader it is clear that John belongs to the Jewish God, his Law and his prophets, but after John came Jesus preaching the gospel, consistent with reply Jesus gave John’s disciples. Again John is placed before Jesus’ time, and is past tense.

Sect Leader

Returning again to the passage in Luke 7:18-19, what is striking about the account of John inquiring about Jesus is that the in having disciples it tells us John is a sect leader (e.g., πρωτοστάτην τῆς τῶν αἱρέσεως, "heresy" in the sense of Acts 24:5), someone of great stature, who is in some ways equal to Jesus here.

John’s role as a sect leader, in Christian terms a bishop, included establishing doctrine and practices for his followers. This is reflected in the question put to Jesus in Luke 11:1, recorded in Adversus Marcionem 4.26.1,

Cum in quodam loco orasset ad patrem illum superiorem … aggressus eum ex discipulis quidam, Domine, inquit, doce nos orare, sicut et Ioannes discipulos suos docuitSo it was that John, at some time in the past, taught his disciples prayers. It is a challenge the author feels obliged to have Jesus answer with his own prayer (Luke 11:2-4), as any sect leader and teacher – but one who would be above all authority of any bishop – down to explicitly stating a creedal prayer. What the content of John’s creedal prayer was we will likely never know.

When in a certain place he had been praying to that Father above … one of his disciples came to him and said, "Lord, teach us to pray as John also taught his disciples."

Another aspect of John’s teaching was his baptism, discussed in Jesus’ question to the Chief Priests, scribes, and elders, in response to their inquiry about the source of his authority in the passage of Luke 20:1-8. [9]

"Was the baptism of John from heaven or from men?"This baptism of John’s was to this point previously not mentioned in this gospel. It should be noted Jesus refers to it in the past tense, something which has occurred at some previous time. The response of the Pharisees (using Tertullian’s language) is of no help, as they cannot decide which source was John’s. [10] While no doctrine is explicitly associated with John’s baptism we can infer from the Marcionite Apostolikon on the Baptism of Christ what may have been in common with John’s.

We find in 1 Corinthians 1:10-13, speaking of divisions (σχίσματα) in Christianity, tells us these divisions distinguish among themselves by invoking the name of their sect’s Apostle; [11] The Marcionite text for the passage is reproduced here.

I have heard from those of Chloe, that there is strife among you.The sectarian divisions include with them the concept of different baptisms, as attested in Paul’s response. Also associated with the baptism is crucifixion, which we will examine later. The description of Paul and Apollos as sect leaders, where they are ministers or teachers of their followers, is confirmed in 1 Corinthians 3:4-5

One of you says, 'I belong to Paul,' or 'I belong to Apollos,' or 'I belong to Cephas.'

Has Christ been divided? Was Paul crucified for you?

Or were you baptized in the name of Paul? [12]

For whenever someone says, 'I belong to Paul,' and another, 'I belong to Apollos,'In Paul there is a strong association between baptism in Christ with death. E.g., Romans 6:3-4,

are you not walking according to men? What then is Apollos, and what is Paul?

Teachers, through who you believed (διάκονοι δι᾽ ὧν ἐπιστεύσατε)

Do you not know that all of us who were baptized into Christ Jesusand again in Colossians 2:12, which associates baptism with the circumcision of Christ not made with hands.

were baptized into his death?

Therefore we were buried with him through baptism into death

ἢ ἀγνοεῖτε ὅτι, ὅσοι ἐβαπτίσθημεν εἰς Χριστὸν Ἰησοῦν,

εἰς τὸν θάνατον αὐτοῦ ἐβαπτίσθημεν;

συνετάφημεν οὖν αὐτῷ διὰ τοῦ βαπτίσματος εἰς τὸν θάνατον

'having been buried together with him in baptism'The baptism of Christ is clearly a way to associate symbolically with Jesus’ death and burial. And the death of Jesus, to the Marcionites and others, was how he paid ransom to ruler of the earth to purchase our souls. In short it was the embodiment of his mission. Another baptism is spoken of in 1 Corinthians 10:1-2, [13] with the same terminology (e.g., ἀγνοεῖν) we find in Romans 6:3-4

συνταφέντες αὐτῷ ἐν τῷ βαπτισμῷ

For I do not want you to be ignorant, brothers,This baptism of Moses is metaphorical. It speaks of the baptism of the forefathers into the covenant of Moses, representing circumcision with hands, and the Laws of the creator God given by Moses. This does not go well, as verse 10:5 tells us that the Jewish God "found no pleasure with most of them." The baptism of Moses then is different, but it was synonymous with his mission.

that all our fathers were under the cloud and all passed through the sea,

and all were baptized into Moses in the cloud and in the sea

Οὐ θέλω γὰρ ὑμᾶς ἀγνοεῖν, ἀδελφοί,

ὅτι οἱ πατέρες ἡμῶν πάντες ὑπὸ τὴν νεφέλην ἦσαν καὶ πάντες διὰ τῆς θαλάσσης διῆλθον,

καὶ πάντες εἰς τὸν Μωϊσῆν ἐβαπτίσθησαν ἐν τῇ νεφέλῃ καὶ ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ

So what was the baptism of John then? We can assume like Jesus it is associated with his mission. And so the question put to the Chief Priests, the scribes, and the elders, was whether the mission of John was from heaven or men is asking if it was divine or not.

Measuring John

And again returning to the passage in Luke 7:18-19. The author of the text has John admit his inferior status as a teacher and sect leader to Jesus, by having his disciples asking the question. The very question itself is an intriguing one. 'Are you he who is to come, or look we for another?' It tells us that John himself is looking for a Christ to come, one who is predicted. In the 2nd century the Marcionites interpreted this statement as proof that Jesus was from a different God, not the Jewish God of the Law and prophets that John knows, and because of this fact John did not know who Jesus was.

Although Jesus does not say so outright, it appears in Marcion’s text he did not accept John’s mission as from heaven where he came from. This sentiment seems clear enough in Jesus’ follow to his response to John’s question. In verse 7:23, as reported in Epiphanius Panarion 42.11.8 [14]

'Blessed is he who shall not be offended in me,'

μακάριος ὃς οὐ μὴ σκανδαλισθῇ ἐν ἐμοί·

"What did you go out into the wilderness to behold? A reed shaken by the wind? What then did you go out to see? A man clothed in soft clothing? Behold, those who are gorgeously appareled and live in luxury are in kings' courts. What then did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet. This is he of whom it is written, 'Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, who shall prepare thy way before thee.' I tell you, among those born of women none is greater than John; yet he who is least in the kingdom of God is greater than he." [15]The initial statement about a reed blowing in the wind is meant as a put down, giving an assessment of John as somebody unimportant. In the next line it is surprising to say the least to have Jesus to then ask if people went out to behold a finely dressed man and living among the king’s courtesans. This runs smack in the face of every preconceived notion we have about John as an impoverished outsider to the powerful. We like to think of these two lines as set up for the punch line to follows, as tongue in cheek, but there are no throwaway lines in the gospel all contain some theological significance. John is shown here to be aligned with the world’s wealth and powers, an alignment with those of the demiurge in Marcionite terms.

And when Jesus says that yes John is a prophet, we already know that it should be aligned with the same powers, the same God of creation and the Law. This is confirmed by saying John is not just any prophet, but the one written about in Malachi 3:1. The significance of this statement in Marcion’s text cannot be understated. This is not the scripture of Jesus’ God but of the Jewish God. Yet Jesus is confirming that John is the last prophet of the Creator before the end times (e.g., Malachi 4:5). But he does not accept him as belonging to him. When he says he is the greatest born of women, he is saying that although he ranks highest among the Jewish God’s elect, he is not in the Heaven of his God, and that even the lowliest follower of Jesus, who would be the least in God’s kingdom, is greater. And they are so because the least of his God is greater than the greatest of the demiurge.

The Malachi 3:1 association of the final prophet with John [16] brings to the fore the question of whether the Baptism scene was posterior to Marcion’s gospel or if the scene was dropped by the Marcionite author in the composition of his gospel. To determine this we need to look at the presentation of John in the other gospels.

| Graphical View of my Synoptic Gospel Model |

View from Matthew and Mark

Matthew was written after Marcion’s gospel, deliberately modifying both the content and sequence of his gospel. Mark shared a common prototype gospel (“M”) with Matthew, but had the lightest theological editorial layer of any Gospel, with the fewest extraneous expansions added to its sources. As a result Mark in many places represents the earliest version of certain passages. And because Mark shares an underlying prototype gospel with Matthew, it will help identify Matthew’s expansions on the text. So we will examine John’s portrayal in these two gospels together, pointing out differences between them along the way.

Mark opens by showing an awareness of the last prophet association with John, in the famous attribution of Malachi 3:1 to Isaiah in verse 1:2, [17] an addition not found in Matthew’s parallel account. This tells us it was not part of the original narrative from the proto-gospel. This bears some investigating, as it specifically ties John to the last prophet motif in Malachi 4:5. But before we do that we need to look at the common elements in John’s introduction.

Mark’s introduction appears more likely original, setting aside Malachi 3:1 for the moment,

As it is written in Isaiah the prophet, "Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, who shall prepare thy way; the voice of one crying in the wilderness: Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight--"Matthew’s appears secondary, because he introduces the passage concerning John’s identity with,

"For this is he who was spoken of by the prophet Isaiah when he said"This betrays contact with the Marcionite text of Luke 7:27 which maps John to Malachi 3:1, "This is he of whom it is written" (οὗτός ἐστιν περὶ οὗ γέγραπται). But Matthew is presenting a different picture of John than Marcion’s gospel, one largely shared by Mark –or perhaps their common source–, but with certain specific anti-Marcionite features not found in Mark, as we shall see.

Οὗτος γάρ ἐστιν ὁ ῥηθεὶς διὰ Ἠσαΐου τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος

Both gospels portray John preaching in the wilderness immediately prior to the start of Jesus’ mission. Matthew 3:1 adds that the wilderness of Judea, geographically problematic. Matthew 3:2 says that John called people to "repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand." Mark 1:4 says that John 'preached a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins.' This seems a conflation of two distinct practices, preaching and baptism. In both accounts John Baptizes in the Jordan, saying that people come from Jerusalem and Judea, which is to the south, to be baptized by him in the Jordan. These accounts have literalized the baptism of John to the Christening act or ritual we know today. This is very different than the Marcionite reading of baptism as symbolic of Christ death and burial, as discussed above with respect to Romans 6:3-4 and Colossians 2:12, implying that John’s baptism is referring to his death. By contrast the Christian baptism, performed by John before Jesus begins his mission strikes me as not right. This is explained (Mark 1:4, Matthew 3:6) as a baptism associated with the confession of one’s sins.

Mark 1:7-8 gives the more plain account of John’s preaching content,

And he preached, saying, "After me comes he who is mightier than I, the thong of whose sandals I am not worthy to stoop down and untie. I have baptized you with water; but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit."The key point Mark is making is that Jesus, who has not yet arrived, is far mightier than John. John then compares his baptism as mere water, while Jesus’s is with the spirit. Jesus’ baptism is however a reference to his death and burial, as we saw in Romans and Colossians. That doesn't seem to be the case anymore with John’s baptism. And this seems to be confirmed when John Baptizes Jesus in Mark 1:9-11 with the immersion water baptism of Jesus. Here the spirit, which one presumes will be what Jesus baptizes with, descends upon him "like a dove." Jesus never baptizes in Marcion’s gospel, [18] nor is there mention of this baptism in Matthew. For now it is a dangling concept.

Matthew deals slightly differently with John’s baptism and preaching. First before John says a mightier one is to come, in Matthew 3:7-9 he blast the Pharisees and Sadducees who came out to be baptized, saying to them,

"You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit that befits repentance, and do not presume to say to yourselves, 'We have Abraham as our father'; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham. Even now the axe is laid to the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.What is it that gives the Pharisees this unworthiness in Matthew’s eyes? The answer is found in Matthew’s rewrite of second woe to the lawyers – that is teachers of Mosaic Law; an allegorical stand-in Jewish Christian opponents for the Marcionite audience – found in Luke 11:47-48 [19] saying that the lawyers build tombs for the prophets whom their fathers killed. In Marcion’s gospel the charge would have been seen building the tombs for the prophets as analogous to venerating the books of the law and prophets. The version in Matthew 23:29-36 see the subject changed from lawyers to instead scribes and Pharisees, when Jesus says,

"Woe to you scribes and Pharisees; hypocrites! For you build the graves of the prophets and adorn the tombs of the righteous, then you say, 'If we had lived in the days of our fathers, we would not have partaken with them in [shedding] the blood of the prophets.' Therefore you testify that you are sons of those who murdered the prophets. Fill up, then, the measure of your fathers. You serpents, you brood of vipers, how are you to escape being sentenced to hell? Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will scourge in your synagogues and persecute from town to town, that upon you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of innocent Abel to the blood of Zechari'ah the son of Barachi'ah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. Truly, I say to you, all this will come upon this generation."Matthew has changed the tombs (μνημεῖα = 'monuments') for the prophets to their graves, and instead assigns the building of tombs to be for the righteous. This breaks the association with the books of the Prophets, just as changing the subject of the woe from the teachers of the Law to the Pharisees, breaks the association the heretics saw with the orthodox "Jewish" Christians who taught the Old Testament books like the Jews. Jesus in Matthew 23:30-31, like John in verse 3:7, does not believe the claim of Jewish religious leaders that they are different than their ancestors, which can only mean they don’t accept Christ. The association with the murder of the prophets is the guilt of the priestly class of Pharisees (and Sadducees) spoken of as "children" of vipers in verse 3:7 is made clear in verse 23:33 where they are called the "offspring" of viper by Jesus. Just as John asked them who warned them of the wrath, so here Jesus asks them "how are you to escape being sentenced to hell?" And what righteous and what prophets were murdered? Matthew tells us one was Abel, the righteous one, who was killed by his brother Cain in Genesis 4:8. The other is Zechariah, the prophet, stoned to death by command of Joash (Jehoash) the king in 2 Chronicles 24. [20]

The final association of the killing of the prophets and John in Catholic thought is found in Romans 11:2-3, referencing 1 Kings 19:10, stating,

Do you not know what the scripture says about Elijah, how he pleads with God against Israel? 'Lord, they killed your prophets, tore down your alters and left only me behind, and seek my life'The association of Elijah with John is complete in Matthew 11:14 (see below), so it would be clear that John would be aware of the same guilt association. And returning to John’s preaching in the Jordan, when he addresses the Pharisees and Sadducees that came out to be baptized, he states a winnowing fire is coming, which recalling the last prophet, is the warning of the fire of the last day in Malachi 4:1. So indeed John declares in Matthew 3:11,

"I baptize you with water for repentance, but the one coming after me is stronger than me, whom I am not worthy to remove his sandals. He will baptize you with Holy Spirit and fire, of whom his winnowing fork in his hand, and he will thoroughly cleanse his threshing and gather his wheat into the barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire."We have then the baptism of fire, and it is clearly linked to the passage of Malachi 4:1 (3:19 LXX) in view

"For behold, the day of the lord is coming, burning as a furnace and engulfing them, and all the foreigners and all those acting lawlessly will be like chaff and kindling set afire; and the day is coming when they will be set ablaze says the lord of hosts, "so that it will leave them neither root nor branch." [21]The Septuagint reading targets specifically for destruction on the day of the Lord, those who oppose to Mosaic Law (ὁ ποιέω ἄνομος). The description matches with the Marcionites and most Gnostic Christians, who rejected the Jewish God and with him the Mosaic Law. Given the direct challenge Matthew’s gospel puts forth against the Marcionite gospel, it is extremely likely he had this reading in mind when he wrote verse 3:12. [22]

We confirm Matthew’s focus by comparing the earlier Marcionite text in Luke 16:16-17 here

The law and the prophets were until John; since then the gospel of the kingdom of God is preached, and every one enters it violently. But it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away, than for one stroke of my word should fail. [23]But reading Matthew 11:12-14 the emphasis is completely different

From the days of John the Baptist until now the kingdom of heaven has suffered violence, and men of violence take it by force. For all the prophets and the law prophesied until John; and if you are willing to accept it, he is Eli'jah who is to come.Marcion’s gospel emphasized the difference by stating that while the law and prophets ended with John, it is Christ’s word which continues. Matthew took Jesus’ word out as well as the comment about the gospel being preached after John to remove separation the Marcionite writer put between the Jewish scriptures of the law and prophets and the gospel, which parallels the separation of the Jewish God’s heaven from the previously unknown Christian God’s heaven. Matthew of course has no separation, and that’s is shown in his depiction of the kingdom of heaven suffering violence not only now that Christ has appeared, but also when John was preaching, for Matthew held both were from the same God. And he goes further, making completely clear that indeed John is not just a prophet fulfilling Malachi 3:2 in verses 11:9-11, but is in fact Elijah from Malachi 4:5-6 (LXX 3:22-23)

Behold, I am going to send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and terrible day of the lord. He will restore the hearts of the fathers to their children and the hearts of the children to their fathers, so that I will not come and smite the land with a curse.In Matthew John is Elijah returned and his preaching repentance was saw in verse 3:11 is so that Jews can avoid the wrath to come "of the great and terrible day of the lord" Malachi speaks to. And this is what John refers to when he said to the Pharisees and Sadducees who came out to be baptized, "Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?" Even though they are Jews who claim Abraham as their father, Matthew singles them out as not worthy of his baptism. He requires that they prove themselves by "producing fruit worthy of repentance," which can only mean accepting Christ.

Mark 1:6 and Matthew 3:4 talk about John’s clothing and diet

And John was clothed with camel's hair, and had a leather belt around his waist, and ate locusts and wild honeyThese describe a simple outfit of a prophet of old, and a subsistence diet of insects and bee honey that is gathered wild. This portrayal seems to specifically designed to counter the luxurious portrayal of John as one wearing fine clothes and living, and so dining, among the King’s courtesans from the Marcionite text of Luke 7:25 and its parallel in Matthew 11:8. And that image of a subsistence lifestyle and modest clothing of John’s succeeds in eviscerating the luxurious living mention from our minds even today.

The last element about John not found in Marcion is the beheading scene found in Mark 6:17-29 and Matthew 14:3-12. The original gospel text, as represented by Luke 9:9 simply has Herod, when told that some people had said Jesus was John raised from the dead, responding, "I beheaded John." This was too pregnant a concept not to have been expanded upon in the common source of Matthew and Mark when the character of John took on this much larger role than he had in the Marcionite gospel. It is no surprise both Matthew and Mark place this beheading tale immediately after Herod’s comment.

The beheading account is a highly theatrical one. First the gospel source, borrowed from Josephus Antiquities 18.5.4 its cast, as we can see from this passage

But Herodias, their sister, was married to Herod [Philip], the son of Herod the Great, who was born of Mariamne, the daughter of Simon the high priest, who had a daughter, Salome; after whose birth Herodias took upon her to confound the laws of our country, and divorced herself from her husband while he was alive, and was married to Herod [Antipas], her husband's brother by the father's side, he was tetrarch of Galilee; but her daughter Salome was married to Philip, the son of Herod, and tetrarch of Trachonitis;These gospels get the story wrong, as it is not Philip (aka Herod Philip) who marries Herodias in contradiction to the laws of the Jews, [24] but rather after her divorce she married Philip’s half-brother Herod Antipas. But the reversal of marriage order may well have been to give Herod a reason to want to silence any Jewish critics of his family’s contravening of the law. And similarly John was then said to have opposed Herodias’ marriage to her living first husband’s brother. And so motive is given for Herod to arrest John. Finally the daughter of Herodias, unnamed in Matthew’s account, is identified in Mark as the same Salome from Josephus’ account. Matthew’s account has her uncle, Herod the Tetrarch, was so pleased with her dance he offered here anything. Mark would add dialogue for Herod – a king for Mark – by quoting Esther 5:3 the offer to Queen Esther from King Mordecai, "whatever you desire, I will give you, even half my kingdom." Although obviously Herod as a Roman appointed Tetrarch would have no such authority over the territory assigned him – another sign Mark mistakes Herod for his father. Although colorful a story, there is no theological significance in it as far as John goes, except he is the representative of the Law.

I covered the rebuke of John in my prior article on the authorship of the fourth gospel. But it gets right to the point. Matthew, as stated above, develops on the last prophet when after repeating Malachi 3:1 in verse 11:10, has Jesus state plainly in verse 11:14, that John is Elijah from Malachi 4:5, the last passage of the Old Testament.

"And if you are willing to accept it, John himself is Elijah who was to come."This position is outright rejected in the Gospel of John, and is reflected in verse 1:21 when the Jews, after asking John if he was Christ, then ask if he is Elijah, which he then answers in the negative,

And they asked him, "Who then? Are you Elijah?" and he said, "I am not."This position not only contradicts Matthew’s presentation, but also the understanding in the Marcionite gospel, Luke 7:26-27, that John was indeed a prophet, and indeed the last prophet. That is the last prophet of the creator God of the Law and the prophets from Luke 16:16. John however rejects entirely Jewish scriptures, and so his John is somebody else entirely. To see who we go back to the prologue verse 1:6-8 [25]

"Are you the prophet?" and he answered, "No."

There was a man (ἄνθρωπος) sent from God, whose name was John. He came for testimony (μαρτυρίαν), to bear witness (μαρτυρήσῃ) to the light, that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to bear witness to the light.John is apparently an 'ordinary' man sent by the God of Christ, not the Jewish God. [26] His role to testify about the light, which was previously unknown, but now come into the world; to identify Jesus as the light. And through his testimony as a witness people can believe in him. And in verse 1:15 in identifying the Christ he says,

"This was he of whom I said, 'He who comes after me ranks before me, for he was before me.'"Now I am ignoring looking back before the event happens in verse 1:15 and the circular reference at verse 1:30 looking back again to this verse, clear sign of later redaction. What we see is both John bearing witness of Jesus as the light, and also his confirming that Jesus existed before he appeared. This is one of many subtle points of departure from Marcionite theology. This role of testimony is critical in John’s complex argument, fulfilling a legal requirement of more than self-testimony. John’s testimony is brought forth in verses 5:33 for this purpose. And we see it is necessary for John to bear witness because Jesus is unknown to the Jews –as you would expect the alien God’s Christ to be– as he tells the Pharisees when they ask why he baptizes not being a prophet nor the Christ (of the Jewish God) they expect in John 1:24-27

Now they had been sent from the Pharisees. They asked him, "Then why are you baptizing, if you are neither the Christ, nor Elijah, nor the prophet?" John answered them, "I baptize with water; but among you stands one whom you do not know, even he who comes after me, the thong of whose sandal I am not worthy to untie."Curiously in this gospel John does not Baptize Jesus. His witness is simply recognizing him in verses 1:29-31

The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him, "Behold, the Lamb of God ... This is he of whom I said, 'After me comes a man who ranks before me, for he was before me.' I myself did not know him; but for this I came baptizing with water, that he might be revealed to Israel." [27]John is thus said to have fulfilled his witness role as defined in 1:6-8, in the passage from verse 10:41-42

And many came to him; and they said, "John did no sign, but everything that John said about this man was true." And many believed in him there.As in Marcion’s Gospel, the fourth gospel never refers to John as "John the Baptist." But baptism as we saw above is a key feature as in all the gospels. But in John there is another feature, the transfer of disciples directly from to Jesus [28] as in verse 1:35-37

The next day again John was standing with two of his disciples; and he looked at Jesus as he walked, and said, "Behold, the Lamb of God!" The two disciples heard him say this, and they followed Jesus.This disciple transfer does not occur in the Synoptic accounts, and we see in fact the differences between the practices of the disciples pointed out in the Marcionite gospel (Luke 5:33; also Matthew 9:14/Mark 2:18). In the Marcionite gospel the dispute is understandable, as these represent disciples of different gods. But in the fourth gospel John is sent by the same God as Jesus. Knowing that, perhaps it’s not so surprising that the dispute the disciples of John find themselves in instead is with a Jew, and instead of fasting it is over purifying in verse 3:25. This leads to the disciples of John asking him about the transfer of his followers’ allegiance to Jesus, presaged earlier by the transfer of disciples, when Jesus is reportedly baptizing, in the passage John 3:22-30.

After this Jesus and his disciples went into the land of Judea; there he remained with them and baptized. John also was baptizing at Ae'non near Salim, because there was much water there; and people came and were baptized. For John had not yet been put in prison. Now a discussion arose between John's disciples and a Jew over purifying. And they came to John, and said to him, "Rabbi, he who was with you beyond the Jordan, to whom you bore witness, here he is, baptizing, and all are going to him." John answered, "No one can receive anything except what is given him from heaven. You yourselves bear me witness that I said, I am not the Christ, but I have been sent before him. He who has the bride is the bridegroom; the friend of the bridegroom, who stands and hears him, rejoices greatly at the bridegroom's voice; therefore this joy of mine is now full. He must increase, but I must decrease."There are several concepts to unpack here as we finish up this gospel. The first is that Jesus baptized. Although we are not told what this baptism involved, it does not seem logical at this stage of the gospel that it involves Jesus’ death and burial. This represents another break with Marcion, as well as with orthodoxy. [29] In contrast to the Marcionite presentation where John was offended at Jesus' rank (Luke 7:23 per Epiphanius), here John embraces Jesus as a friend of the bridegroom, and instead of fasting he is rejoicing. This is not trivial, as a friend is the truest disciple of Jesus in the Gospel of John, and is part of the greatest love commandment in verses 15:11-15, and John’s joy fully embodies the concept which you can read here

These things I have spoken to you, that my joy may be in you, and that your joy may be full. "This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. Greater love has no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends. You are my friends if you do what I command you. No longer do I call you servants, for the servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you.So it is friendship that allows John to happily accept his role diminished as Jesus’ gains. They are from the same God, so it does not represent the demiurge losing to the good God as in the Marcionite presentation. Finally for completeness there is the mention of John not yet being imprisoned, which seems to confirm the presence of the wording of the Marcionite version of Luke 7:18. John agrees with the more orthodox presentation that John was with Jesus before his incarceration. But like the Marcionite, John leaves it dangling, and even more so because there is no mention of John’s death in the gospel. But this is fitting, for John like all Jesus’ friends, including Lazarus, is alive at the gospel’s conclusion.

An Infancy Story

The Gospel of Luke brings the development of John to its final conclusion, with an infancy story. When Luke took upon himself to rewrite the Marcionite gospel in the spirit of his sect’s version of orthodoxy, he devoted almost the entire first and third chapters – excepting the genealogy of Jesus– to John the Baptist’s narrative. This is in addition to absorbing many of Matthew’s elements concerning John. As we have already covered Matthew account, I will focus here on the presentation in chapters one and three.

In the midst of the pre-birth story is a conversation between John’s father to be, Zechariah and the angel Gabriel who tells him in Luke 1:12-17,

"Do not be afraid, Zechari'ah, for your prayer is heard, and your wife Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you shall call his name John. And you will have joy and gladness, and many will rejoice at his birth; for he will be great before the Lord, and he shall drink no wine nor strong drink, and he will be filled with the Holy Spirit, even from his mother's womb. And he will turn many of the sons of Israel to the Lord their God, and he will go before him in the spirit and power of Elijah, to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the disobedient to the wisdom of the just, to make ready for the Lord a people prepared."There are a few interesting concepts here. Luke evokes the passage Numbers 6:2-3 about the special vow of the Nazarites to separate themselves from wine and strong drink, foretelling that his Christ will be from Nazareth. This goes far to explain away the abstinence of John’s disciples in contrast to Jesus’ disciples without accepting the Marcionite analogy in Luke 5:33-35 of a different God. The angel’s statement that John will be possessed with the power and the spirit of Elijah "to turn the hearts of the fathers to the children" is Luke’s way of declaring God has chosen John to fulfill the prophecy of Malachi 4:5 and is Elijah returned.

The passage in Luke 1:35-44 is designed to answer the charge of the Marcionites that John did not recognize Christ. In a most emphatic way Luke sets out to destroy this argument, showing that even John’s mother Elizabeth knew the special child Mary was carrying, as she cries out in verse 1:52

"Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!His father Zechariah, fill with the holy spirit, gives a speech at John’s circumcision, in verses 1:68-79, evoking images from Malachi 4:2, 5 in which he tells his son

"… And you, child, will be called the prophet of the Most High; for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give knowledge of salvation to his people in the forgiveness of their sins"All the elements of John’s preaching are foretold in this infancy tale. And that preaching is almost identical to Matthew, save a few changes. When he cries out "You brood of vipers!" in verse 3:7 he is directing it at the multitude who came out to be baptized, not merely the ecclesiastical elite represented by the Pharisees and Sadducees in Matthew. Luke is really targeting however the entire audience. So the multitude ask John what to do and he gives a series of decrees in verses 3:10-14 which amount to civic expectation of ordinary people (a late Catholic theme we see in Paul as well):

And the multitudes asked him, "What then shall we do?" And he answered them, "He who has two coats, let him share with him who has none; and he who has food, let him do likewise." Tax collectors also came to be baptized, and said to him, "Teacher, what shall we do?" And he said to them, "Collect no more than is appointed you." Soldiers also asked him, "And we, what shall we do?" And he said to them, "Rob no one by violence or by false accusation, and be content with your wages."So by the time Luke’s gospel was written John’s baptism and preaching of repentance is part of the ordinary Christian confessional. Luke also betrays his lateness by echoing the question to put to John by the Pharisees who asked who he was, whether he was a Prophet or Elijah, or perhaps Christ:

As the people were in expectation, and all men questioned in their hearts concerning John, whether perhaps he were the Christ,Dependence on Matthew (and Mark’s) account, specifically the beheading story, when telling of John’s arrest

But Herod the tetrarch, who had been reproved by him for Hero'di-as, his brother's wife, and for all the evil things that Herod had done, added this to them all, that he shut up John in prison.The advancing of John’s incarceration to the baptism scene could explain why mention of it is missing from Luke 7:18 but apparently found in Marcion’s version (per Dialogue Adamantius 1.26), as it would have been redundant. And although Luke kept the Marcionite wording intact in verse 16:16 concerning the Law and Prophets being until John, he modified verse 16:17 to state that rather than Christ’s words, that even should heaven and earth pass away not one letter of the Law would fall out – a mere three letter change τοῦ νόμου for λόγοι μου. By doing this he preserves the Law even after John, the last prophet.

Luke’s presentation then is consistent with his model of possessive spirit, not just with Jesus but with John, and reinforces the Malachi last prophet analogy of Matthew and Mark with rebuttals to key arguments from Marcionite and also the fourth gospel.

Summary and Conclusions

The story of John and the presentation is very much wrapped up and inseparable from each evangelist’s theology. This analysis of the text of each gospel in turn reveals a process of expansion and theological adjustment that went on from one gospel to the next. So it is no surprise John plays a very different role in the gospels of Marcion, John, and the canonical Synoptics. But this only becomes clear when one separates each account and examines them independent of each other and contrasts their presentation. One thing which did emerge which surprised me somewhat was that the proto-gospel "M" common to Mark and Matthew, appears to have been formed after the Marcionite gospel, as both Matthew and Mark contain certain of the exact same elements of John’s story which are dependent on Marcion’s account and which counter the Marcionite gospel. The development of the beheading of John into the Salome dance story is one such example. The gospel of John, as in so many other elements clearly has refuting Matthew’s gospel in the presentation of John. But the fourth gospel also betrays several elements that while heretical are clearly at odds with the Marcionite sect.

What it tells us about John the Baptist is that the story grew over time and in detail as each evangelist added his opinion. John’s character grew precisely because it addressed the issue of whether Jesus was fore announced. For the Marcionites he represented the end for the old Jewish God’s prophets, as the one called in Malachi, and he showed the incompatibility of the old and the new. While for Mark and Matthew he represented a sentinel prophet promised in Malachi, bringing back Elijah. For John he was a witness for the new God and his Christ, who had nothing to do with Elijah or any of the Jewish God’s prophets. Luke reinforced the presentation of Matthew and Mark, but with his own Holy Spirit emphasis and Adoptionist like elements.

My take away is John seems to represent some current Prophet who was about in the days of Tiberius’ reign, whether real or not, who was known to the audience as having been imprisoned and beheaded. From there the story grew, and the moniker "the Baptist" stuck sometime in the late middle part of the 2nd century.

Footnotes:

[1] Adversus Marcionem 4.11.5, ' nobody could have challenged the disciples of Christ, as they ate and drank, to a comparison with the disciples of John, who were constantly fasting and praying' (nemo discipulos Christi manducantes et bibentes ad formam discipulorum Ioannis assidue ieiunantium et orantium provocasset). It’s seems unlikely the disciples of the Pharisees were part of the original verse, but were added later. The Pharisees do not constitute sect leaders like John does, making it a nonsensical addition.

[2] Marcion’s Gospel is missing all Luke 1:1-4:15 entirely, except the mention of Tiberius’ reign from verse 3:1, including all the birth and childhood of John, as well as the Baptism scene on the Jordan. In addition Zahn concludes verses 7:29-35 were not in Marcion, a conclusion which I concur and follow here. John does appear in Marcion in Luke 5:33-35 (5:36-38 should be seen in context), 7:18-19 (possible variance), 22-28, 9:7-8, 9:18-22 (verse 9:20 – τοῦ θεοῦ per AM 4.21.6 and AD 2.13), 11:1-4, 16:16, 20:1-7

[3] Adversus Marcionem 4.21.1-2 attests to this passage. I deleted “the tetrarch” ὁ τετραὰρχης from the address of Herod in Luke 9:7 as this is drawn from Luke 3:1 and used to distinguish from King Herod mentioned in Luke 1:5, neither of which is in Marcion’s account. Had it been present in the proto-Gospel it is inconceivable Mark 6:14 would make the error of calling Herod King. While Tertullian does not mention John being killed, and his allusion to his death at Herod’s hands in AM 4.34.8-9 is clearly drawn from the Catholic text not the Marcionite, both Matthew 14:2 and Mark 6:16 have Herod state, “this is John the Baptist … raised from the dead.” In my judgment that was the original text the Marcionite editor changed here.

[4] DA 829c: Ἐν τῷ εὐαγγελίῳ λέγει ὁ Χριστός· Τίνα με λέγουσιν οἱ ἄνθρωποι τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀθρώπου; λέγουσιν οἱ μαθηταί· Ἰωάννην τὸν βαπτιστήν, ἀλλοι δὲ Ἠλίαν, ἄλλοι δὲ ὅτι προφήτης τις τῶν ἀρχαίων ἀνέστη. εἶπε δὲ αὐτοῖς· Ὑμεῖς δὲ τίνα; ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ Πέτρος εἶπε· τὸν Χριστόν. (2.13 Rufinus) In euangelio dicit Christus: Quem me dicunt esse homines, filium hominis? Dicunt ei discipuli: Alii Iohannem baptistam, alii Heliam, alii quia propheta aliquis antiquus surrexit. Dixit auten ad eos: Uos uero, quem me esse dicitis? Respondens Petrus dixit: Tu es Christus.

The text agrees with Matthew 16:13 with Jesus identifying himself as the son of man, and asking who do “men” say I am (also Mark 8:27), and the answer from Peter as simply "The Christ" is confirmed by Mark 8:29. Adversus Marcionem 4.21.6 supports the reading of simply "Christ" Petrus ... interrogant domino quisnam illis videretur, ... responderet, Tu es Christus. These were likely original. I question the identification of John as the Baptist (Ἰωάννην τὸν βαπτιστήν) as this moniker otherwise never appears in Marcion.

The text agrees with Matthew 16:13 with Jesus identifying himself as the son of man, and asking who do “men” say I am (also Mark 8:27), and the answer from Peter as simply "The Christ" is confirmed by Mark 8:29. Adversus Marcionem 4.21.6 supports the reading of simply "Christ" Petrus ... interrogant domino quisnam illis videretur, ... responderet, Tu es Christus. These were likely original. I question the identification of John as the Baptist (Ἰωάννην τὸν βαπτιστήν) as this moniker otherwise never appears in Marcion.

[6] Marcion’s reading of Luke 5:36-38 is one such example which conforms to the text of Matthew 9:17 and 9:16

[7] Luke 5:17-29 the healing of the paralyzed man; Luke 5:12-17 cleansing of the leper; and Luke 7:11-15, the raising of the dead man in Nain. The blind receiving sight does not occur until Luke 18:35-42, the healing of the blind man (Epiphanius 42.11.6.51, Adversus Marcionem 4.36.9-11, also Dialogue Adamantius 5. 14), prompting the Lukan redactor to insert verses 7:20-21 including the passage και τυφλοις πολλοις εχαρισατο βλεπειν to make the statement of Jesus giving the blind sight had happened before John’s disciples asked.

[8] See Adversus Marcionem 4.33.7-8, Epiphanius Panarion 42.11.6.43; for its use by Marcionites and other heretics to denote a break between the past for a new God, see Adversus Marcionem 5.14.6-7 on Romans 10:4, Acta Archelaus 40 for examples.

[9] Tertullian quotes baptisma Ioannis unde esset. Luke 20:1-8 appears to be identical in Marcion, except that Tertullian, per Adversus Marcionem 4.38.1-2, indicates that those questioning Jesus were Pharisees rather than "the chief priests, and the scribes and the elders." However Tertullian speaks the same way in his book On Baptism chapter 10 he also refers to those challenging Jesus in this passage as Pharisees, and he is clearly using the Catholic text. In the Gospel of John the elders (πρεσβυτέροις), scribes, and chief priests are stand ins for the orthodox hierarchy the author of John opposes. I have not investigated if the same is true in Marcion.

Note wording of the question may match Matthew 21:25 as Tertullian reads unde esset with Matthew (Vulgate unde erat) which conforms to + πόθεν. But this is not at all decisive, as Tertullian paraphrases.

Note wording of the question may match Matthew 21:25 as Tertullian reads unde esset with Matthew (Vulgate unde erat) which conforms to + πόθεν. But this is not at all decisive, as Tertullian paraphrases.

[10] The internal debate with no answer from the ecclesiastical establishment opponents to Marcion’s Jesus likely reflects confusion over doctrine on the matter of John in the 2nd century. Nearly identical uncertainty is found also in the accounts from Mark and Matthew indicating it was long standing, present even in the proto-Gospel.

[11] Tertullian confirms this understanding of Paul on heresies (sects) in Adversus Marcionem 5.8.3 Saepe iam ostendimus haereses apud apostolum inter mala ut malum poni.

[12] The Marcionite text is attested in Dialogue Admantius 1.8 (Adamantius) quotes 1 Corinthians 1:11-12, ἤκουσταί μου, φησίν, ὑπὸ τῶν Χλόης ὅτι ἔριδες εἰσιν ἐν ὑμῖν· ὃς μὲν γὰρ ὑμῶν λέγει· ἐγὼ μέν εἰμι Παύλου, ἐγὼ δὲ Ἀπολλῶ, ἐγὼ δὲ Κηφᾶ. μεμέρισται ὁ Χριστός; μὴ Παῦλος ἐσταυρώθη ὑπὲρ ὑμῶν, ἢ εἰς τὸ ὄνομα Παύλου ἐbαπτισθητε; Rufinus (DA) reads, perlatum est enim mihi, inquit, de vobis ab his qui sunt Chloes quia contentiones sunt in vobis, et alius dicit: Ego sum Paulis, alius: Ego Apollo, alius: Ego Caphae, Diuisus est Christus? This reflects – ἀδελφοί μου and unmentioned by Clabeaux, without support, but I think correct – ἐγὼ δὲ Χριστοῦ as it makes no sense that there would be such a sect against those of Paul (Marcionite), Apollos (speculatively Appelles), and Cephas (Catholic) represent known camps. Unlike those you are baptized in Christ name, but not Paul, et al (verse 1:13b)

[13] The passage is quoted in full from Dialogue Adamantius 2.18 and Epiphanius 42 (see footnotes 81-85 of my reconstruction of the Marcionite 1 Corinthians for details)

[14] Epiphanius states the phrase is altered, and we notice it reads - ἐὰν, changing the sense from “blessed is anyone who is not offended in me” to “blessed is he who is not offended by me.” 'Blessed is he who shall not be offended in me,' making it so the text refers to John (Παρηλλαγμένον τό μακάριος ὃς οὐ μὴ σκανδαλισθῇ ἐν ἐμοί· εἶχε γὰρ ὡς πρὸς Ἰωάννην). Tertullian understands Marcion’s text the same way, reading in AM 4.18.4 that ‘But John is offended, when he hears of the miracles of Christ, as of an alien god.’ Sed scandalizatur Ioannes auditis virtutibus Christi, ut alterius.

[15] This entire passage of Luke 7:24-28, excepting verse 7:25, is explicitly attested in Marcion by Epiphanius and Tertullian. Verse 7:25 fits grammatical form and is was copied into Matthew as well, so I accept it as original.

[16] Thomas Thompson's book, The Messiah Myth, is an excellent resource to understand the imagery in the NT. Of special interest concerning the role of John the Baptist in the gospel, see chapter 2, pages 27--66, Figure of the Prophet

[17] Like Marcion’s gospel and John’s gospel, Mark does not quote the Old Testament, and the few quotes he has can be attributed to his source documents.

[18] Luke 12:50 is not attested in Marcion. Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.29.12-13, covers verses 12:49 and 12:51 without mention of 12:50 or Baptism. Dialogue Adamantius, 2.4 has the Catholic champion Adamantius quote Luke 12:49 after Matthew 10:34 with the same sense. Luke 12:50 is likely part of the Catholic redaction in order to map the passage to Matthew 3:11/Luke 3:16.

[19] Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.27.7-9, attests verse 11:47 (also Panarion 42.11.6.27) and 11:48 and confirms that lawyers refer to those who are teachers of the Law of Moses. Epiphanius, Panarion 42.11.6.28, states Luke 11:49-52 was not present

[20] Neither of these killings truly should fall upon the Jewish religious class represented by the Pharisees and scribes. Abel and Cain were sons of Adam and Eve, predating Abraham and thus the Jewish descendants. The killing of Zechariah could more accurately be pinned on the king and his royal court than either the Jewish people or their priests. But such was the early church’s view.

[21] Wording is Septuagint, 'all the foreigners and all those acting lawlessly' καί εἰμί πᾶς ὁ ἀλλογενής καί πᾶς ὁ ποιέω ἄνομος, against the Masoretic 'and all the arrogant and every evildoer' והיו כל זדים וכל עשה. The wording fits Matthew’s Jewish Christian opinions.

[22] For examples of Matthew’s use of Marcion see my blog entry, The Antithesis and the Relationship of Matthew 5:3-45 to Marcion.

[23] Marcion reads λόγοι μου for τοῦ νόμου, per Adversus Marcionem 33.9 Transeat igitur caelum et terra citius, sicut et lex et prophetae, quam unus apex verborum domini; also Luke 21:33, Matthew 24:35, and Mark 13:31 also attest to this reading as original.

[24] Per Leviticus 18:16 and 20:21; clear and direct evidence that the Law in Judea province was indeed Mosaic or Torah Law.

[25] I do not include John 1:22-23 in this analysis, as it is a redundant question added by a later redactor to harmonize John with the other gospels, having him proclaim himself the one spoken of in Isaiah 40:3. Nowhere else does John have the OT speak of the characters of Christ’s God, and not used in an antithesis exegesis.

[26] Irenaues show in Adversus Haereses 3.11.4, that he is fully aware the heretics (Valentinians) argued from this passage in John that John the Baptist was from the high God and not the Demiurge, when he asks, "John, the forerunner, who bears witness of the Light, from which God was he sent?" Praecursor igitur Johannes, qui testatur de lumine, a quo Deo missus est? Irenaeus then argues from a harmonized view the position of the Catholic Synoptic Gospels, Luke 1.17 specifically, that despite the explicit rejection in the fourth gospel, that John the Baptist is Elias/Elijah,

[28] The most notable of being Simon Peter; whom Jesus refers to as "Simon son of John" (Σίμων ὁ υἱὸς Ἰωάνου). But I do not hold great stock in Simon being a disciple of Jesus in the original version of this gospel. And specifically the association of Simon to John, as this occurs in verse 1:42 and the appended chapter 21 (21:15-16) only, making it suspect. If Simon were added in a later layer, in order to be a first disciple as in the other gospels would require him to have transferred over from John.

[29] The gospel of John having Jesus baptize was enough of an embarrassment that the catholic editor felt compelled to add verse 4:2 parenthetically explaining away issue by saying that Jesus himself did not baptize, rather his disciples.

[19] Tertullian, Adversus Marcionem 4.27.7-9, attests verse 11:47 (also Panarion 42.11.6.27) and 11:48 and confirms that lawyers refer to those who are teachers of the Law of Moses. Epiphanius, Panarion 42.11.6.28, states Luke 11:49-52 was not present

[20] Neither of these killings truly should fall upon the Jewish religious class represented by the Pharisees and scribes. Abel and Cain were sons of Adam and Eve, predating Abraham and thus the Jewish descendants. The killing of Zechariah could more accurately be pinned on the king and his royal court than either the Jewish people or their priests. But such was the early church’s view.

[21] Wording is Septuagint, 'all the foreigners and all those acting lawlessly' καί εἰμί πᾶς ὁ ἀλλογενής καί πᾶς ὁ ποιέω ἄνομος, against the Masoretic 'and all the arrogant and every evildoer' והיו כל זדים וכל עשה. The wording fits Matthew’s Jewish Christian opinions.

[22] For examples of Matthew’s use of Marcion see my blog entry, The Antithesis and the Relationship of Matthew 5:3-45 to Marcion.

[23] Marcion reads λόγοι μου for τοῦ νόμου, per Adversus Marcionem 33.9 Transeat igitur caelum et terra citius, sicut et lex et prophetae, quam unus apex verborum domini; also Luke 21:33, Matthew 24:35, and Mark 13:31 also attest to this reading as original.

[24] Per Leviticus 18:16 and 20:21; clear and direct evidence that the Law in Judea province was indeed Mosaic or Torah Law.

[25] I do not include John 1:22-23 in this analysis, as it is a redundant question added by a later redactor to harmonize John with the other gospels, having him proclaim himself the one spoken of in Isaiah 40:3. Nowhere else does John have the OT speak of the characters of Christ’s God, and not used in an antithesis exegesis.

[26] Irenaues show in Adversus Haereses 3.11.4, that he is fully aware the heretics (Valentinians) argued from this passage in John that John the Baptist was from the high God and not the Demiurge, when he asks, "John, the forerunner, who bears witness of the Light, from which God was he sent?" Praecursor igitur Johannes, qui testatur de lumine, a quo Deo missus est? Irenaeus then argues from a harmonized view the position of the Catholic Synoptic Gospels, Luke 1.17 specifically, that despite the explicit rejection in the fourth gospel, that John the Baptist is Elias/Elijah,

"Truly it was by Him, of whom Gabriel is the angel, who also announced the glad tidings of his birth: [that God] who also had promised by the prophets that He would send His messenger before the face of His Son, who should prepare His way, that is, that he should bear witness of that Light in the spirit and power of Elias."Utique ab eo cujus Gabriel est angelus, qui etiam evangelisavit generationem ejus: qui et per prophetas promisit angelum suum missirum ante faciem Filii sui, at praeparaturum viam ejus, hoc est, testificaturum de lumine, in spiritu et virtute Heliae.[27] I have difficulty accepting John 1:32-34 as part of the original, as it is redundant, harmonizing this account to the synoptic gospels. It’s not certain "who takes away the sin of the world!" was present in John’s first version. I wonder also if 'the lamb of God' ὁ ἀμνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ was not originally 'the holy one of God' ὁ ἅγιος τοῦ θεοῦ (cf Mark 1:24/Luke 4:35). It’s a mere two letter change.

[28] The most notable of being Simon Peter; whom Jesus refers to as "Simon son of John" (Σίμων ὁ υἱὸς Ἰωάνου). But I do not hold great stock in Simon being a disciple of Jesus in the original version of this gospel. And specifically the association of Simon to John, as this occurs in verse 1:42 and the appended chapter 21 (21:15-16) only, making it suspect. If Simon were added in a later layer, in order to be a first disciple as in the other gospels would require him to have transferred over from John.

[29] The gospel of John having Jesus baptize was enough of an embarrassment that the catholic editor felt compelled to add verse 4:2 parenthetically explaining away issue by saying that Jesus himself did not baptize, rather his disciples.

Good to see you back at it Stuart!

ReplyDeleteWhen he says he is the greatest born of women, he is saying that although he ranks highest among the Jewish God’s elect, he is not in the Heaven of his God, and that even the lowliest follower of Jesus, who would be the least in God’s kingdom, is greater. And they are so because the least of his God is greater than the greatest of the demiurge.

ReplyDeletethe least...: ''Paulus''??? (rhetorical question)

In your view, was the earliest ur-Gospel (L or M) written before the earliest 'pauline' letter ?

Is it possible to know, from your view, who, between the later authors/redactors, i.e. Marcion and his opponents, remained more faithful to the oldest gospel (M & L)? Coincidentally (!) it seems that your assumption that the oldest gospel are actually two (M and L) is made partially for not answering this question. But prima facie it seems to me that the proto-orthodox versions are always those that occurred after, or to break what the Marcionites united, either to bind what the Marcionites divided. For example, prof Vinzent thinks that the catholic anti-Judaism was a reaction to alter-Judaism of Marcion & company (and what Matthew did about John, in your view, is further confirmation of this). My question is: what if, instead, the embryo of all the stories were already anti-Jewish even before the Marcionites wanted serenely to say farewell to Judaism (therefore with the Catholics restoring de facto, contra Marcion, the old anti-Jewish view of first Christians) ?

These are my suggestions, by now. Thanks for your inspiring post!

Giuseppe

Guiseppe,

ReplyDeleteAfter looking at John the Baptist elements I have come to the conclusion that "M" came together as single document after the Marcionite gospel was in circulation. But it's compositional history is clearly complex, as we can tell simply looking at it mechanically. Specifically the doublet section in Matthew and Mark, which I Farmer referred to as the four thousand loop (from the feeding of the four thousand). This seems to have been stand alone and a source for John, and fused together in "M." (To answer an earlier question, no it does not line up with John's signs - I do not believe "signs" is any more real than quelle). The main part of "M" is derived from "L", perhaps a wild version, with different voice in some passages. That however is merely a mechanical answer to what they proto-gospels were.

The Pauline letters, even in Marcionite form are a collection, basically tracts, from multiple authors, some of which even in Marcionite form draw pastiches from prior "letters", which were put in letter form. Mechanically the Marcionite collection appears to have come together in one or two prior forms before the ten letter collection form.

Which came first? Well the collection form and Galatians are definitely after the Marcionite gospel.My suspicion is the Corinthians are also posterior. So if I had to guess I'd say "L" was likely earlier, but not "M" (for mechanical reasons). Both the Paulines and gospels evolved in the same time frame. Galatians knows of at least two Gospel, the Marcionite and either Matthew or Mark.

This gets back to the core question, what were the gospel for? If you look at the earliest ones, they are basically dialogue form. This makes me suspect they were religious plays, similar to other cults in the Roman Empire. The gospel writings are "book form" which go through the "movie" initiates watched. Remember most people were illiterate, so the play was a favorite form of religious instruction going back to the Greeks. My suspicion is that they weer not performed as plays much if at all, and the literary form as scripture instead took hold.

Vincent's opinions require a full analysis for me to comment meaningfully. But I think he has jumped to motives and conclusions without collecting all the facts. He's closer than most, but he still missed the bullseye.

regards,

Stuart

ugh, this blog doesn't let me edit my comments to take out typos.

Delete- "I Farmer" should be "Farmer"

- "Galatians knows of at least two Gospel" should be "gospels"

- "weer not performed" should be "were

About Vinzent, I am curious especially about a very specific point raised by him.

ReplyDeleteHe writes:

The earliest author after Marcion to relate narratives of the Gospels is Justin, and before him, perhaps, Aristides.

(Marcion and the Dating, p.227)

About Aristides, precisely:

To conclude, the dating of Aristides' Apology is difficult, but the dedication to Antoninus Pius is more likely to be historical than to ones to Hadrianus, especially ad the latter could be influenced by Eusebius' account.

(p. 234)

And final observations:

Without making a decision here, it seems at least dangerous to conclude from this state of textual evidence that Aristides is our first witness for the title 'Gospel' for a written document (S against A), and to draw from what follows (that Jesus was pierced - S - or nailed - A - by the Jews; tasted death - G) that Aristides reflects knowledge of John. He may, but he may not.

(p. 251)

according to your views on Aristides, what is your view?

1) he is basing on one of the gospels already written even if you do not know which one.

2) he isn't basing on any written gospel, but simply reflects the belief held by earliest Christians.

3) he is basing on John's Gospel.

Thanks for any reply,

Giuseppe

Your questions on Aristides I'll answer indirectly. But when you read below you'll understand why I would not doubt he had contact with the Catholic revision of John, which is after even Luke, maybe even 3rd century.

DeleteI have become extremely suspicious in recent days about the writings of Irenaeus. There are certain elements in Adversus Haeresies which appear to be from a much later era. There are the incongruities of the material which appears to be about herectics which is first hand and about their systems. And then there are a few heresies drawn from NT texts, which simply makes no sense to be in the same writer - not his style. Also he defends the Trinity some 50-60 years before other writers know of it. My hunch is, there is original Irenaeus writing in there from the later part of Commodious' reign, but a second hand from the late 3rd or early 4th century is in the text we know. This throws all dating of other fathers based on him in doubt. (I think Irenaeus has a legitimate late 2nd century core and a significant 3rd or 4th century rewrite).

This is important because he is used to date Justin. And that brings me to problems with the two main works of Justin. The apology and the dialogue. The dialogue seems highly fictitous. Justin makes himself the main character and has a stilted conversation full of NT and other quotes from others - not real speech. It's style is similar to Adamantius, which is accurately and tightly dated around 290-305 CE. This makes his dialogue 150 years before any other, when they suddenly became popular in the late 3rd and 4th centuries.

The second problem with Justin is the Apology. If we look at real letters to the Emperor, such as the first 9 books of Pliny (the 10th a medieval forgery), they are very brief and to the point, as one would expect of any petition. This is no different than a memo to the President today. It had better fit on one 8.5" by 11" sheet of paper double spaced, and take no more than three minutes to read and comprehend. Think of the so called elevator speech. The Apology of Justin, and Aristides for that matter, are long exhaustive tracts. And there is nothing in there of interest for the emperor; no specific person to be released, no tax to overturned or lightened, no request for treasury or temple built. In fact there are even insults of past emperors, which is nothing short of blaspheme of the imperial god cult. They also mention Christian heresies, as if a pagan emperor would care about the internal politics of some obscure cult. These read like a paid op-ed in the New York Times. In short, before Constantine an apology to an emperor is hard to imagine. So I think they are from a later era. I notice that Aristides also has contact with the Apostles creed, itself a post Trinitarian document, which pushes it into the 3rd century.

- Stuart

Peter Kirby had a post on his blog today i thought you would find interesting.

ReplyDeleteHi Stuart,

ReplyDeletethe weakest point for me in your solution to the synoptic problem is only the relationship between the letters of 'Paul' and the Gospel of Mark. I'll explain. The recent research has reevaluated not only the gospel of Marcion but also the dependence of the Gospel of Mark on the letters of Paul. But I hear from you that you believe Galatians definitely written by Marcion AFTER Mark and Matthew: how about all literary markan dependencies from Galatians that scholars have reported? Assuming a II CE origins for all the epistles, if it was not Mark copying from Galatians, as claimed for example by Tom Dykstra, then how do you explain all that 'Paulinist' influence in Mark (the fact that the Markan Jesus is paulinized, if not even an allegorized Paul)?

Thanks for any reply,

Giuseppe

Giuseppe,

DeleteI don't see how any relationship to Paul is relevant to intra-Gospel dependencies. It is an independent issue. There has to be an establishment of interaction, and a display of how that would impact the dependency model.

Dykstra bases his work on Goulder's romp, which while an entertaining fiction is not supported critically at any level. There is a complete failure to account for Marcion, and no discipline in differentiating Pauline texts. Pastoral and Lukan elements as well as Acts, are treated as if original. Paul is supposed to be gentile, yet ascribed many post-Marcionite traits, while Peter is given an strange mix of Jewish and Gnostic positions often contradictory. Without better foundation for this its impossible to take Dykstra seriously.

None the less I will give a quick once over addressing the supposed Markan dependence on the Paul. Form my handy RSV bible, I see 10 passages noted as having a parallel in Paul, 5 are derived from double/triple traditions, which really is not significant. Still let's go through them one by one: (next reply)

1) Mark 4:11 has a reference to "those outside" (τοῖς ἔξω). This is Mark's adjustment to Luke 8:9-1/Matthew 13:13ff. It concerns church relations with non-Christians; a pastoral concern, absent from Marcion. 1 Thessalonians 4:12 reflects this post Marcionite concern with church image. The passages in Colossians 4:5 also post-Marcionite Catholic layer, dityo 1 Corinthians 5:12-13 (see my reconstruction). See also 1 Timothy 3:7

Delete2) Mark 7:5 perhaps refers to Jesus being a Pharisee. Galatians 1:14 is a later Catholic addition, marginally related, where the post-Marcionite Catholic redactor shows Jesus as being Jewish. Gospel came first in this case.

3) Mark 7:18-19 adds "he declared all foods clean" and not in Matthew's account. The cited passage of 1 Corinthians 10:25-27 is part of a Catholic insertion, not in Marcion (see my reconstruction notes on 1 Corinthians). Romans 14:14 is uncertain, might be of Valentinian origins. Mark closely matches Acts 10:15. An indication that Mark is not Jewish, but this position is not at all inconsistent with the understand of post-Marcionite Catholic texts. Possibly its a later addition from margins.

4) Mark 7:20-23 a pastoral list of ills. It most closely matches Romans 1:28-31 which is a late pastoral addition, not in Marcion. The Marcionite Galatians 5:19-21 concerns the evilness of the flesh against the spirit, and not defilement.

5) Mark 9:50 on salt and peace is IMO the earlier version of what Matthew 5:13 and Luke 14:34-35 (Marcionite) derived from it. Colossians 4:6 is a pastiche of Mark 9:50, as is 1 Thessalonians 5:13; both are Catholic additions. Dependency is backwards here.

6) Mark 10:11 on divorce is common with all Christian sects, from the common proto-gospels (Matthew 5:32, Luke 16:18) as well as 1 Corinthians 7:10-11. Romans 7:2-3 is different, purely Marcionite with divorce as allegory for when Law applies. Mark adds to his account a Roman understanding, places same admonition on women as on men - note Roman women could also divorce.

7) Mark 12:31 concerns Leviticus 19:18. It comes from triple tradition (Luke 20:39-40, 10:25-18, Matthew 22:34-40), doesn't need contact with Romans 13:9, Galatians 5:14, nor James 2:8. A common position of all Christian sects.

8) Mark 13:33 "be watchful" is vaguely parallel to Ephesians 6:18, Colossians 4:2. But these passages in the Asiatic letters are more likely to be dependent on the gospels.

9) Mark 14:22-25 "drinking the cup" is part of the triple tradition (Luke 22:17-19, Matthew 26:26-29). The citation to 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 is part of the post-Marcionite Catholic redaction to 1 Corinthians (see my reconstruction on the secondary nature of 1 Corinthians 11:23-32). Dependence in Paul is on the Gospels here.

10) Mark 14:36 adds "Abba" (not in Matthew's version) which is identical to Galatians 4:6 (Marcionite) and Romans 8:15 (not attested in Marcion, a pastiche of Galatians). Hum.

Upon examination almost all the dependencies vanish.

- Stuart

According to some scholars, the absence of gospel-quoting in epistles is so much of a truism that it is almost possible to give an approximate date to a work simply by how and to what extent it refers to the Jesus life in a biographical sense. Do you find valid that way of dating texts? If not, how do you explain otherwise the deliberate omission of explicit Gospel-quoting (not only implicit, like I see from your list above), in a marcionite epistle?

DeleteFor example, prof Robert Price wrote:

First, it appears to me both that Marcion is responsible for

significant portions of the epistolary text and that the epistles are

quite innocent of the gospel tradition of sayings and deeds by an

earthly Jesus. Therefore, Marcion not only possessed no gospel

but knew nothing of our Jesus tradition.

(from his essay Early Date for the Pauline Epistles?)

It seems clear that you reject explicitly the Price's premise, and therefore his conclusion, too. Even when you consider a reputed mythicist proof-text like Epistle to Hebrews, do you think that his real author knew about a written gospel ? Which marcionite text do you think is surprisingly silent about a Gospel-Jesus?

Thanks,

Giuseppe